In this post, we decided to present it in an interview style format covering some major themes of the book, particularly the character study of George Washington and Benedict Arnold. During the month of May we read Nathaniel Philbrick’s book Valiant Ambition: George Washington, Benedict Arnold, and the Fate of the American Revolution. Michael is finalizing a mortgage for his new villa, and I had to licensing exams to take. For some books, we create shared notes with outlines for each chapter to help us learn a thing or two. From the shared note for this book, we’ve created this post. The reflection at the end is an example of some of the self-reflective prompts we answer at the end of each chapter. If you’re interested in reading this book and having the reflective chapter outlines, just let us know, and we’ll be more than happy to share. Below is our review on Valiant Ambition.

“He was executed, and yet admired.” That’s how Nathaniel Philbrick opens Valiant Ambition—not with George Washington or Benedict Arnold, but with the gallows walk of Major John André, a British officer facing death for espionage. It’s a scene steeped in dignity, not in glory. And it sets the stage for everything to follow.

Valiant Ambition isn’t a tale of founding fathers wrapped in marble and myth. It is a portrait of two men—Washington and Arnold—whose paths diverge not because of ability, but because of character. One endures slander. The other collapses under the weight of unrecognized merit. One becomes a symbol of the republic. The other betrays it.

What Philbrick gives us is not just history but a mirror. And in that reflection, we can examine the motives behind our own actions.

The Revolution Was a Civil War

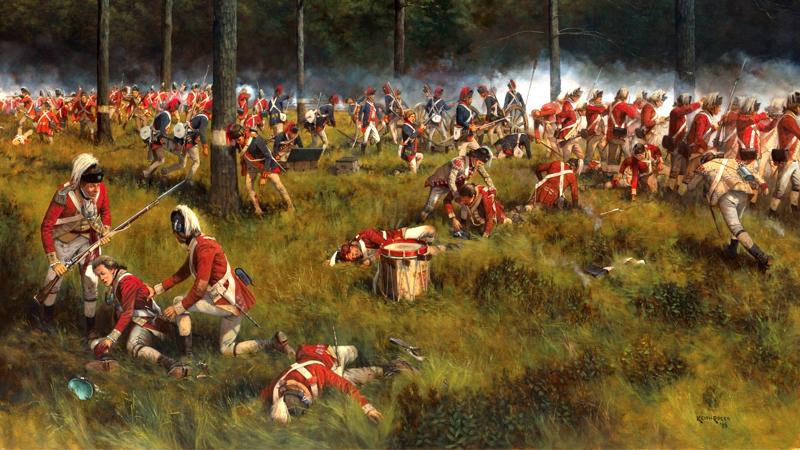

From the outset, Valiant Ambition dismantles the clean, sanitized narratives about the Revolutionary War that many of us grew up with. The war wasn’t a unified stand for liberty; it was a chaotic, personal, often deeply bitter civil conflict.

“The British felt like they were killing their brothers,” Michael observed. “The American farmers were fighting because they were being invaded. It was a war, like all others, started by the rulers and not the ruled.”

André’s execution shows just how blurred the moral lines really were. He died with honor, even as he died a traitor. His conduct evoked ancient virtues—“death before dishonor”—that feel painfully absent from our modern political life.

Philbrick forces us to wrestle with whether loyalty is a virtue, or just another perspective. And that’s the brilliance of starting not with the triumphant, but the tragic death of André.

Arnold: The Hero Before the Fall

One of the most powerful through-lines in the book—and in our notes—is how long it takes for Arnold to actually betray anyone. Long before the treason, there was valor. The Mosquito Fleet on Lake Champlain was desperation turned into ingenuity. Arnold was everything you’d want in a commander: “Resourceful, creative, charismatic, intelligent. By God, he acted like he should’ve been commander in chief.”

And yet, the seeds were already there. “His ambition wasn’t nurtured,” Michael noticed, “and a hero turned to a villain in pursuit of recognition.”

It’s in those cracks between recognition and injustice, between leadership and ego that betrayal festers.

Washington: Steady, Silent, Suffering

In contrast stands Washington, not as a statue, but as a man slowly becoming what history would later need him to be. He begins unsure, even disdainful of his own army. But he grows. He disciplines. He endures.

“He worked at it, every day, in many adverse circumstances,” David wrote. “He wasn’t born with that discipline. He forged it in fire.”

Washington’s greatness doesn’t come from charisma or battlefield brilliance. It comes from presence. From silence when Congress would shout. From restraint when Arnold would rage.

“Leadership is psychological,” David added. “Everyone was looking to him to save them.” And in that silence, in that unflinching steadiness, he did.

The Great Betrayal: When Recognition Never Comes

By the time we reach Saratoga, the tragedy is no longer impending—it’s unfolding. Arnold gives his body to the cause, is wounded, and then is erased from the record. Gates takes the credit. Congress ignores the sacrifice.

“It absolutely ticked me off,” David admitted. And yet, here’s where Philbrick’s story begins to feel more like a moral reckoning than military history. Arnold wanted honor, but what he really wanted was affirmation. Washington endured betrayal, but moved forward. Arnold turned inward. He let bitterness bloom where honor and duty should have been planted. “The tragedy of Arnold begins not in betrayal,” Michael wrote, “but in the slow starvation of unacknowledged excellence.”

That’s not just about war. That’s about work. About family. About all the times we’ve sat in silence while others took the credit. And what we chose to do with that pain.

What We Learned (And What We’re Still Learning)

Philbrick doesn’t offer an easy villain in Arnold or an unblemished saint in Washington. He gives us something more painful, and more useful: a spectrum of character under pressure. Of how men respond when no one claps. When everyone forgets. Washington never wavered in these circumstances but found the ability to endure by leaning on others, Providence, and the task before him. In similar circumstances, Arnold burned with resentment and bitterness. It consumed him.

And that’s the haunting story of Valiant Ambition, how razor-thin the line between a great man and a traitor. It’s not until the job is finished that one can judge whether one did a good job or not. But this book highlights that those who get the job done in an honorable fashion are men who are capable of enduring slander, injustice, and loneliness all along the way—and choose to stay faithful anyway.

Each day that choice is still ours to make.

Final Reflection

Who do you resemble when the world turns quiet?

When your name is left off the report?

When your efforts go unseen, and no one says thank you?

Valiant Ambition is about two men. But it’s also about us.

About how easy it is to become bitter.

And how hard—but how necessary—it is to stay honorable.

Let that be our ambition.

Written by David Coody