I have been a fan of Michael Pollan ever since I read his 2006 work The Omnivore’s Dillemma. In that work, he showed how the food that we eat can have consequences far beyond affecting our health that extends into the political and even ethical realms. By the standards of his previous work, Pollan takes his long-form journalism to a whole new level. His 2018 work, How to Change Your Mind: What the New Science of Psychedelics Teaches Us About Consciousness, Dying, Addiction, Depression, and Transcendence is a unique work that blurs the lines between professional journalism and self-experimentation. The final product is a vulnerable honesty that helped me to recontextualize psychedelics. As a medical professional who does not recreationally partake in hallucinogens, this book was an eye-opening trip.

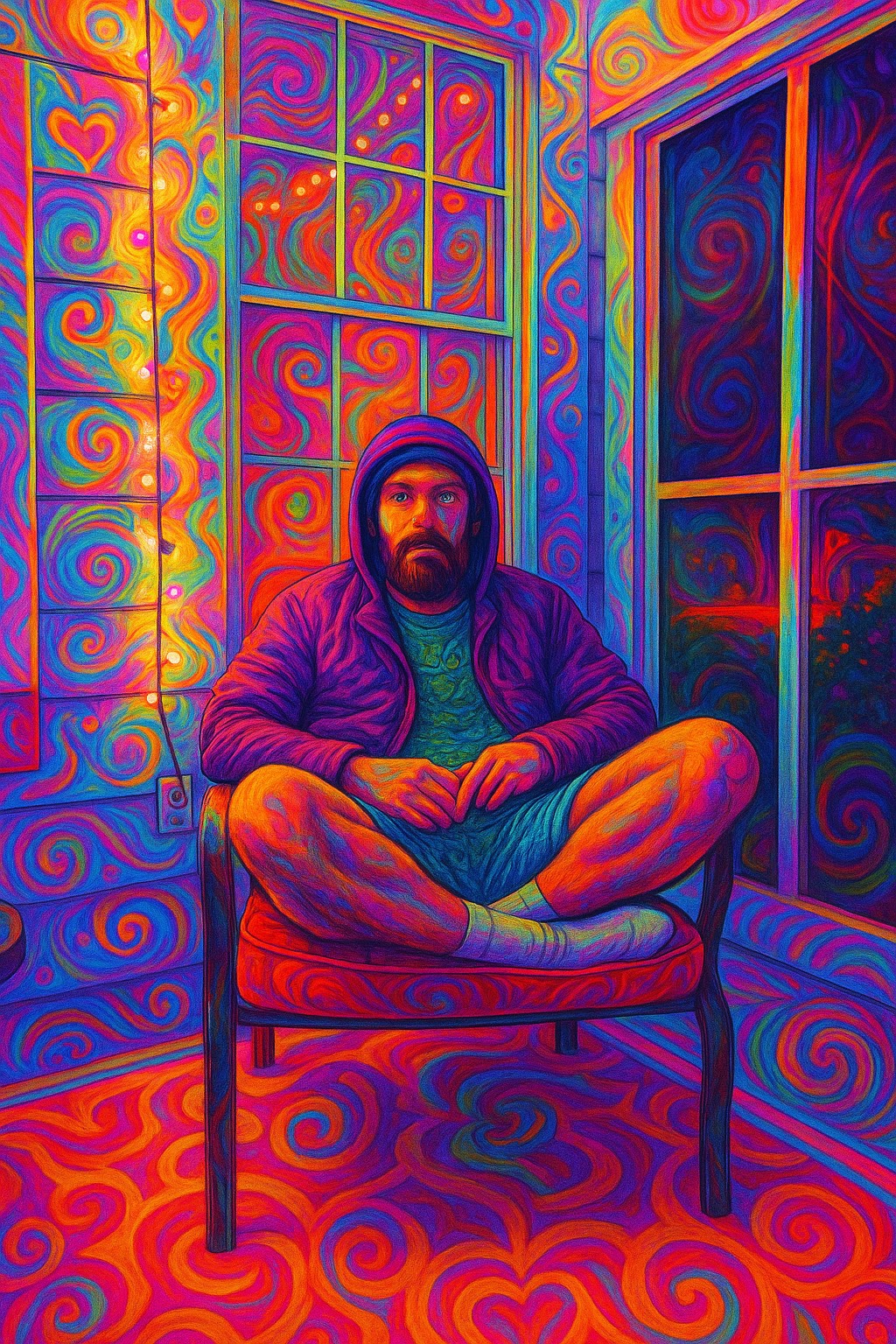

I first heard about this book on the Joe Rogan Podcast [Episode #1121] where Pollan was discussing the book, and I was shocked to hear that Pollan did first-hand experimentation with (almost) all the substances that he writes about. This was especially shocking to me, because Pollan does not strike you as someone who partakes in recreational drugs. Whereas hallucinogens conjure pictures of Scooby and Shaggy in the Mystery Machine or that famous concert at Woodstock, Michael Pollan represents the opposite. He is a mild-mannered, agnostic, bookish, 70-year-old-gentleman with a distinguished career in meticulous journalism.

Pollan admits to his readers at the beginning that he had never previously tried nor had he intended to try hallucinogens. However, in writing his book he did not think that he could give a fair representation of the subject without personal experience with the object at hand. I do not know if I agree with this on principle, as many journalists have written subjects on matters with which they have no personal experience [there have been plenty of journal articles chronicling the feats of astronauts, written by chronic earth dwellers], but I also cannot fault Pollan for using his book as an excuse to indulge in a post-midlife crisis. Here are some of my favorite highlights regarding what he discovered.

The book starts by highlighting three unrelated events in 2006 that triggered a renaissance of sorts in psychedelics. The first was the centennial celebration of the birth of Albert Hoffman, the Swiss chemist who synthesized LSD in 1938 while attempting to create a medicinal compound. He accidentally ingested the compound while in his lab and was the first and probably only individual to have a non-anticipatory acid trip. Hoffman states of the experience: “My ego was suspended somewhere in space, and I saw my body lying dead on the sofa.” This quip paves the way for the important concept that Pollan returns to many times, that both “set” and “setting” are so crucial in determining the quality and outcome of a hallucinogenic trip.

The second coinciding event of 2006 was the Supreme Court ruling in favor of the U.S. religious sect of the Brazilian Church, Union of the Plants [UDV], that they could import and use ayahuasca as a sacrament in the United States. This decision was made in the full knowledge that ayahuasca contains a schedule I substance, dimethyltryptamine [DMT] and the ruling was grounded in the 1993 Religious Freedom Restoration Act. The third event was the publication of a paper by Johns Hopkins researcher Roland Griffiths on psilocybin, in which he makes that case that its use can “occasion mystical-type experiences having substantial and sustained personal meaning and spiritual significance.” This paper was perhaps the first double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical study of a psychedelic in over four decades, and it was met with acclaim from both the academic and the political community and served as a sounding board for future research into medicinal psychedelics.

Pollan spends the rest of the chapter introducing his readers to the history of psychedelics in America up to the present day. I was unaware that Hoffman had his LSD synthesized by the pharmaceutical company Sandoz and distributed as an investigational drug known as Delysid in the 1950s. Later in the 1960s, individuals such as Timothy Leary attempted to bypass the approved pathways and take LSD to the masses, with the catchy slogan to his followers that they should “turn on, tune in, and drop out”. Among other things, his aggressive push to bypass the official channels of rigorous drug research and the ensuing chaos of the 1960s contributed to LSD being outlawed in 1969 and then classified as a Scheduled I controlled substance in 1970.

While the history of psychedelics in America is incredibly interesting, the most impactful content in the book is obviously centered around Pollan’s own experiences with psylocibin, LSD, and 5-MeO-DMT were by far the most interesting. A common theme to his experience with all three was the spiritual and transcendent nature of his trips. This is especially pertinent given that Pollan is decidedly agnostic (and despite having mystical experiences during his trips, he remains agnostic throughout the book).

To help describe what he experiences, he draws from the wording of William James in his book The Varieties of Religious Experiences. The four qualities or “marks” of having a religious experience are 1) the subjective defiance of expression [no way to adequately describe the event], 2) The noetic quality [more on this later], 3) the transient nature of the experience, 4) the passivity of the experience. On the “noetic quality”, James says that subjects feel as if they have been “let in on a deep secret of the universe, and they cannot be shaken from this conviction”. This is further expounded as “ego dissolution,” in which a high dose of psychedelics dissolves the subjective “I” to such an extent that it is impossible to distinguish between what is objectively and subjectively true.

The noetic quality probably sounds familiar to many of us, as it is the exact quality that makes it so easy to roll our eyes at the ramblings of a schizophrenic or a deep-state conspiracy theorist. However, the “ego dissolution” is a concept that gripped me as a compelling and even actionable attribute of psychedelics that we should not easily dismiss. For a period during their trip, the participants can overcome that gnawing, daily, roaring “I” that demands that every interaction and occurrence of every passing moment in the day must be self-referential. It is this same “freedom from self” that Western religion aspires to achieve through prayer and acts of sacrifice, Eastern religion through meditation, and secular religion through mindfulness. Psychedelics are ego-dissolution on rocket-fuel, and the uninitiated can be catapulted into the cosmos if they are not careful.

As best as modern psychology can surmise, our ego is a complex defense mechanism arising from our consciousness to help us not let our guard down amid a world full of potential dangers. The ego is very good at what it does, and for this reason it can seem that everyone around us is self-centered, self-absorbed, and uninterested in the wellbeing of others. Unsurprisingly, the ego puts up a great fight against ego-dissolving psychedelics. To this end, Pollan emphasizes that the physical location with the presence of a qualified guide [set] and the mental state that you bring into the experience [setting] are so key to optimizing a hallucinogenic experience. These two pieces, which are so often neglected, can determine whether someone has a transcendental experience or a “bad trip”. The overwhelming number of individuals being sent to the ER or even hospitalized for their bad trips during the height of Timothy Leary bringing unrestricted hallucinogens to the masses was a manifestation of the dangers of partaking in non-structed psychedelics.

Even with the proper precautions, Pollan describes his 5-MeO-DMT trip as “a terrifying experience I would not wish on anybody” in which he was “sent through the universe strapped to the front of a nuclear missile”. Upon emerging on the other side, he described “extreme terror and dissolution of self” followed by being “reborn into the world with immediate gratitude”. As best as I can surmise, the ego fights these experiences so vehemently because they simulate death and the hereafter. This should not come as a surprise when considering that DMT is made endogenously in small amounts in the mammalian brain’s pineal gland. According to a 2019 University of Michigan study, rats showed a transient spike in endogenous DMT concentrations in their brains around the time of death.

There are so many fascinating stories from this book that I do not have time to cover, such as the jolly, eccentric mycologist Paul Stamets and his journey in the Pacific Northwest with Michael Pollan to find the blue Psilocybe azurescens affectionately known as “azzies”. Stories such as his almost make you want to get out a field guide and go searching for homeopathic remedies for all internal maladies growing underneath a sturdy redwood. However, I would like to close this post with a brief discussion of the Default Mode Network [DMN].

In layman’s terms, the DMN is a complex, interconnected network housed within our brains that helps us create our internal narrative and dialogue which is used in the construction of our sense of self. DMN helps center us in relation to others, allows us to remember the past and to think about the future, and also to play out theoretical scenarios. It is largely inactive in children until their school years, and the DMN is disrupted in individuals with Alzheimer’s and autism spectrum disorders. There are many potential clinical implications for psychedelics, but one of the most profound is their role in tampering a hyperactive DMN .

I found the fact that the DMN is largely inactive in children to be so telling for the mechanism by which psilocybin can be helpful. Pollan describes the pathways in the brain like a path in a downhill slope that has been carved out by repetitively sledding downhill on that slope. The path has been taken so many times by adulthood, that even if an individual tried to “mentally sled” down an adjacent path, they would be pulled back into the familiar path and sled down it yet again. Children have not gone down the mental hill enough times to have carved out a path, which is why their brains are so much more impressionable. It is for this reason that they can easily acquire new skills such as learning an instrument or a new language. Conversely, older individuals seem stuck in their ways and are less likely to try things outside of their comfort zone [new food, music, hobby, etc]. Psychedelics can help individuals “shake the snow globe” and reset these well-worn paths in the brain so that people can get “unstuck” from these entrenched mental ruts and return to a childlike suggestability.

The DMN is hyperactive in both anxiety and depression, and reduced blood flow has been observed in areas of the DMN with administration of psychedelic drugs. This has profound clinical applications in both diseases. A very helpful framework that he gives for depression and anxiety, are that they are akin to fraternal siblings in the family of mental health disorders. Both conditions are symptoms of a mind that is plagued by rumination, albeit at different points in time. “Depression is a response to past loss, and anxiety is a response to future loss… both reflect a mind mired in rumination, one dwelling on the past, the other worrying about the future. What mainly distinguishes the two disorders is their tense.” Prior to reading this book, I had never thought of this helpful framework of these two being the fraternal twins of rumination.

The clinical applications for psychedelics are abundant, and the field has only just begun to scratch the surface of possibilities for mental health therapies. Psilocybin is being studied as treatment for end-of-life anxiety and existential distress, with evidence showing that psilocybin-assisted therapy does reduce the fear of death, anxiety, and depression in terminal cancer patients. In essence, it helps patients to find a sense of peace and acceptance regarding their terminal diagnosis. Psilocybin has also been shown to produce rapid and sustained effects on treatment-resistant depression, as well as addiction and OCD. These last two are interesting, as they both are described as a rigid pattern of self-entrapment, of which psilocybin dampens the DMN and allows patients to free themselves from these unproductive and at times self-destructive patterns.

While I do believe that there is immense value in the further exploration of psychedelics and their implications for pharmaceutical options for patients with mental health disorders or existential dread in the face of terminal diseases, I do not necessarily condone the use of these drugs outright. From the perspective of curiosity, I am glad to have been able to read Pollan’s journey without necessarily needing to go on a similar journey myself. I believe that the “lessons” of psychedelics can be accessed through less extreme (and more legal) pathways, such as mindfulness, prayer, and meditation. However, I do endorse the core tenets of the discoveries.

We occasionally need to have our egos dissolved and to look about and realize that we are not the center of this universe. We should be mindful that the universe existed before us, and that it will continue to exist after us as well. We should call to mind that only a relative handful of individuals will even take notice of our existence or inevitable passing. A trip is not necessary to slow down and live in the present moment, to appreciate the interconnectedness of all things, and to comprehend the transience of the present. I am thankful to live in a time where authors such as Michael Pollan are reminding us that these lessons have timeless value.

Written by Cal Wilkerson