On the theme of colonial revolutionary movements, I recently read Marie Arana’s excellent biography, Bolívar: American Liberator. The book was highly engaging from beginning to end, and through it I learned for the first time about one of the greatest and undoubtedly most undervalued figures of modern history and his quest to free the South American colonies from Spain – Simón Bolívar.

Though he has been referred to as the George Washington of South America, that comparison is not quite fair to either man. Both exhibited greatness and are rightly viewed as fathers of nations, but their ethos, personas, and outlooks were quite different. When the military career of Bolívar was over, the territory that he had liberated was seven times larger than the Thirteen Colonies. Bolívar’s military career was twice as long. After five years of bloody struggle against the Spanish, the population of Gran Colombia was one and a half times more than that of North America, and that land mass that it encompassed was comparable to the size of modern Europe. The conquests of Bolívar surpassed those of Napoleon at the height of his power. Like Napoleon and unlike Washington, he came to an ignominious end. Marie Anana presents such a compelling narrative for this powerful figure in Latin American history, known affectionately by many as “The Liberator”.

The relationship between Spain and its South American colonies was fundamentally different than that between Britain and their North American Colonies. There was a much more heterogenous population as well as a nuanced power structure interwoven with the Catholic Church. At the top were the Spanish born colonists who were appointed by the crown as colonial overseers. Next were the Creoles, those of Spanish descent who were born in the colonies. Then came the pardos which encompassed a mixed-race population that was either mestizo (part-white, part-Indian), mulatto (part-white, part-black), or sambo (part-black, part-Indian). Of course, there existed every conceivable admixture within this schema, and the civilizations of Latin America shortly became some of the most ethnically complex on earth.

Bolívar’s paternal ancestor came directly from Spain to Venezuela, but he was born a Creole in the provincial capital of Caracas on July 24th, 1783. He possessed a title of nobility and was immensely wealthy from birth. His family had several assets including plantations, slaves, haciendas, mines, and political influence. Tragically, his father died of tuberculosis when he was three and his mother died of the same disease when he was six. He and his siblings were taken into the guardianship of his uncle.

While he had a tumultuous relationship with his uncle, his education was well provided for, and he was given the philosopher tutor Simón Rodríguez. He was sent to Spain at the age of 16 to continue his education in the classics and literature. While there he made his way to the court of Queen Isabella II and even played a game of badmitton with her son Prince Ferdinand VII. This young prince was highly insulted when he lost the game, and in a stroke of historical irony he would money of Spain’s South American holdings to him in a few decades.

Bolívar met his wife, María Teresa Josefa Antonia Joaquina Rodríguez del Toro Alayza, while in Spain. She was of the Spanish upper class and the match was well paired given his considerable holdings in Venezuela. They traveled back to Caracas after the marriage, but the scythe of tragedy was ever hanging over those whom Bolívar loved most. She died of yellow fever after eight months of marriage. This death shook him to the core, and he vowed to never marry again. He technically kept this vow, but it did not dissuade him from having many wanton encounters throughout his lifetime. Most of these were very superficial but a few were more impactful, such as the infamous Pepita and the fiercely loyal Manuela Sáenz.

After his wife died, he returned to Spain to grieve her and then took something akin to the modern Euro trip with a few of his closest friends. While this was initially meant to be a distraction from bereavement, it ended up being a formative experience. The spirit of revolution was alive in France at the time, and during his travels Bolívar was present for Napoleon’s self-coronation both in Paris and then again in Rome. He saw firsthand the regression of a revolution based on the Enlightenment concepts of liberty and opposition to tyrannical monarchy. While in Rome, Bolívar took a pledge on the hill of Monte Sacro that he would free the Spanish colonies from their oppressor. Symbolically, this was the same hill on which the plebians pledged to overthrow the patricians of ancient Rome. From this point on, he would never be the same.

That is not to say that he was instantly successful. He made the pledge in 1805, and he led several failed liberation attempts in Venezuela afterwards. His next five years would include a trip to Charleston and Philadelphia where he got to see the nascent colonies fresh from their victory. A fellow revolutionary named Francisco de Miranda attempted to lead a revolution in Venezuela in 1806 with the secret backing of the United States. This proto-revolution ended disastrously, and it led to embarrassment for the United States as they continued to court Spain for a purchase of Florida. This also highlights that the United States has been attempting subversive statecraft in Venezuela for over 200 years. Bolívar joined Miranda on his second revolutionary attempt from 1810-1812 to no avail, and Bolívar retreated into the Caribbean.

While nursing his wounds and plotting his next move in 1815 in Jamaica, he penned his “Letter from Jamaica”, in which he calls Spain the “wicked stepmother” laboring to reapply her chains after the colonies had already tasted freedom. He explains that his people are “neither Indian nor pardos nor European, but an entirely new race, for which European models of government are patently unsuitable”. It was here that the tendrils of despotism began to creep in to his political philosophy, as he insisted “a firm executive who employed wisdom, dispensed justice, and ruled benevolently for life” may be necessary.

He also prophetically predicted the future of many Latin American countries post-revolution in his letter. He penned that Mexico would opt for a temporary monarch, which it did when Maximillian, Archduke of Austria, briefly became its king in 1864. He envisioned that Central America would become a loose federation of states, foreshadowing the Federal Republic of Central America. He noted that because Panama was situated at a “magnificent position between two mighty seas” that it would be the future site of a canal. He foresaw that Argentina would have a military dictatorship. For Peru, he correctly anticipated the privileged white aristocracy would not tolerate true democracy with the liberated people of color within the country, and that rebellion would be a constant threat.

Bolívar returned to Venezuela for another attempt at liberation, but instead soon found himself fighting for the independence of New Granada, which we today know as Colombia. The fight for Colombian independence is where he really came into his own as a military leader who led his men by example and exhibited feats of endurance and strength that his opponents did not think were realistic. He traversed the length of the Magdalena River inland to the coast, braving crocodiles, snakes, and swarms of mosquitoes.

The Liberator passed from fame into legend in the summer of 1819 when he led his men for two months over the Paramo de Pisba Pass in the Eastern Andes. This crossing conjured up images of Hannibal crossing the Alps on his way to the gates of Rome, but at 13,000 feet the Andes passage was at even greater heights. This daring crossing positioned his men behind enemy lines and set the stage for the decisive Battle of Bóyaca on August 7, 1819, in which the Colombians won their independence from Spain.

After Bóyaca, the dominoes began to fall for The Liberator. Venezuela won its independence at the Battle of Carabobo on June 24, 1821. Bolívar was named the first President of La Gran Colombia and given full control of the liberating army. He continued into modern day Ecuador to ensure that the Quito was secured from Spain, and the liberation of Ecuador was completed at the Battle of Pichincha on May 24, 1822.

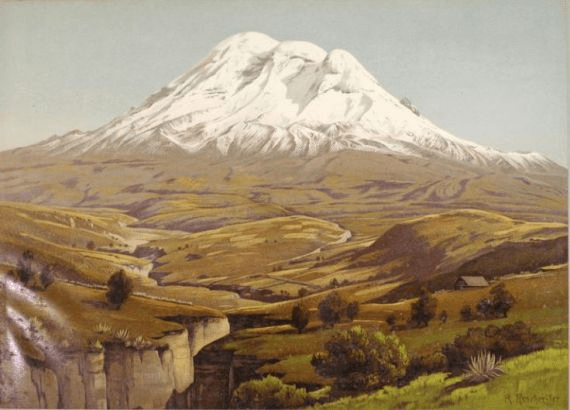

His time in Ecuador, amidst the ashen slopes of the volcanoes, was pivotal for Bolívar’s rising and falling action. In Ecuador, “soaring mountains grazed the vaulted skies – taunting ambition with magnificent zeniths”. One such volcanic peak was Chimborazo, which by the reckoning of the time was the tallest peak on earth [being on the equator and as measured from the center of the earth]. Here, Bolívar began to either be affected by altitude sickness and had slipped into a hypoxic delirium, or he began having true visions of the grandeur that was available to him at this juncture in his life. He had accomplished his original goal of liberating his home country, but for some men contentment is a fleeting fancy.

It was here that his legacy began to diverge sharply from that of George Washington’s. His eyes began to flame with the volcanic fires of Chimborazo as he reflected on his bloody journey from coast to coast. Continuing his conquest further south was inevitable, though he had the express disapproval of the government of Gran Colombia to press on. While wrestling with the gravity of his decision, he wrote a letter to his old teacher, Simón Rodríguez, entitled “Come to Chimborazo”.

Tread, if you dare, on this stairway of Titans, this crown of earth, this unassailable battlement of the New World. From such heights will you command the unobstructed vista; and here, looking on earth and sky – admiring the brute force of terrestrial creation – you will say: Two eternities gaze upon me: the past and the yet-to-be; but this throne of nature, like its creator, is as enduring, as indestructible, as eternal, as the Universal Father.

Hotly debated is whether he also wrote the “phantasmagoric” prose poem depicting his rise to glory entitled “My Delirium on Chimborazo”. Here, he is outside of time, astride the pinnacle of the volcano, and looking upon the past as it unfurls into the future. “A febrile ecstasy invades my mind. I feel lit by a strange, higher fire”. At 20,565 feet, it seems improbable that The Liberator climbed this peak at the zenith of his military glory and penned this beautiful poem. Still, there are many scholars of Latin America who maintain that he did, and it certainly adds a mystique to his lore.

The military campaign raged on as Bolívar unsurprisingly continued further south to liberate Peru. He raced to liberate Peru before the Argentinian general San Martin could claim it for the newly freed southern coalition. Spain was being squeezed from the south by San Martin and the north by Bolívar and was not long for the continent at this point. The politics between The Liberator and San Martin are fascinating, and San Martin ultimately ceded control of Peru to Bolívar. San Martin famously said “there is not room in Peru for both Bolívar and myself.. he will stop at nothing.” After a decisive victory at the Battle of Ayacucho on December 9, 1824, the Empire of the Sun was under Bolívar’s control.

In Washington, DC, on January 1st, 1825, Henry Clay stood at a dinner in honor of the Marquis de Lafayette and proposed a toast “to General Simon Bolívar, the George Washington of South America!” Notably present at this dinner were then President Monroe, John Quincy Adams, and Senator Andrew Jackson. As Marie Arana aptly states: “Not Alexander, not Hannibal, not even Julius Caesar had fought across such a vast, inhospitable terrain. Charlemagne’s victories would have had to double to match Bolívar’s. Napoleon, striving to build an empire, had covered less ground than Bolívar, struggling to win freedom”.

Yet for all of this, he could not help but to continue to push ever further south, into what was then known as Upper Peru. After the Battle of Tumusla on April 1, 1825, this swath of land was liberated and aptly named the Republic of Bolivar. Today, we know it as the country of Bolivia. He debated going even further inland into modern day Paraguay, but he did not want to get into a potential border conflict with Argentina and the Portuguese holdings in Brazil. As inconceivable as it was for him to stand down and return to Colombia to begin governing, the endless war trail was finally over.

The ultimate dream of Bolívar was to see a United States of South America to rival its colossal northern counterpart. He attempted to make this dream a reality by organizing the Congress of Panama on June 22, 1826, on the Isthmus of Panama. There is speculation that this had a symbolic heralding back to the ancient Greek Amphictyonic League which met on the Isthmus of Corinth. Unfortunately for Bolívar, the deliberations were disastrous, and no consensus could be met between those represented [Peru, Venezuela, Panama, Ecuador, New Granada, Mexico, and the Federal Republic of Central America]. The United States sent two delegates, but one died on the journey over, and the other arrived after the meetings were adjourned.

For all his military genius, Bolívar struggled mightily with the work of governance that followed. His liberated countries could never quite get settled. This was perhaps owing to the heterogenous populations or the sudden plunge into democratic egalitarianism as slavery was swiftly abolished once freedom from Spain was won. Bolívar was a military man and no statesman. His inability to reconcile the new post-revolution world of South America in addition to his reluctance to cede power contributed to an uncomfortable and recurrent precedent of declaring emergency dictatorial powers to avoid a constitutional crisis for the sake of the country.

He came into conflict with nearly all the men whom he had fought alongside with once they came into their respective roles as presidents of their new republics under the broader governance of Gran Colombia. Effective presidential power of Colombia had been given to Santander. Paez was in control of Venezuela; General Flores was in power in Ecuador; Aguero in Peru; and Antonio Jose de Sucre in Bolivia. He began to feel a loosening grasp on the reins as these men and their countries took on a direction of their own, somewhat outside of the bounds of what Bolívar had envisioned. An assassination attempt in September 1828 left The Liberator even more paranoid, bitter, and disillusioned. He had also begun to die a slow death from tuberculosis, as his parents had, and the toil on his body was unforgiving.

Bolívar blamed Santander for the assassination attempt, and he exiled him from Colombia. The political winds soon turned against Bolívar, and he was effectively exiled himself soon after. He decided to make his way to the Atlantic coast to recover from his physical ailments and await a boat to take him to Europe. As he had done so many times, he debated once more seizing emergency powers over the army and imposing his will on the countries that were defying him again. Reflecting on this pattern in his life, he mused: “My doctor often told has told me that for my flesh to be strong, my spirit needs to feed on danger. This is so true that when God brought me in to this world, he brought a storm of revolutions for me to feed on… I am a genius of the storm.”

The storm was winding down, and his days were numbered as consumption wrecked his body. The Marquis de Lafayette wrote a letter to Bolívar around this time that he treasured very much. Notably, the family of George Washington also wrote a letter to Bolívar in which they affectionately affirmed him as the “Washington of the South”. Lafayette takes it farther in his letter, and he claims that Bolívar accomplished far more than Washington.

Bolívar freed his people in more difficult circumstances. In North America, the revolutionaries were uniformly white and shared a common ideal and an overwhelmingly Protestant faith. Bolívar had wrested freedom from an amalgamation of European, African, and Native residents spanning the economic spectrum across more varied terrain. This glowing praise was tempered by a reprimand. He warned Bolívar that the lifetime presidency that he had proposed in his constitution was undemocratic. He also urged Bolívar to forgive, pardon, and bring home Santander.

While on his deathbed and reflecting on two decades of rule, in a bitter letter to General Flores, Bolívar came to these ominous conclusions:

- America is ungovernable

- He who serves a revolution ploughs the sea

- All one can do in America is leave it

- The country is bound to fall into unimaginable chaos, after which it will pass into the hands of an undistinguishable string of tyrants of every color

- Once we are devoured by all manner of crime and reduced to a frenzy of violence, no one – not even the Europeans – will want to subjugate us

- Finally, if mankind could revert to its primitive state, it would be here in America, in her final hour

This bitter end may come as a surprising departure from the hopeful delirium of Chimborazo, but it must be appreciated that despite decades of war and toil Bolívar was essentially broke, inglorious in the countries he had liberated, and with no heirs or living family members. According to the famed Colombian novelist Gabriel Garcia Marquez, his last words were, “how will I ever get out of this labyrinth?” Though their veracity is debatable, it is haunting to imagine Bolívar reflecting on his personal life, political woes, and fight against tuberculosis as a maze from which he could not find an escape. He died near Santa Marta on the coast of Colombia on December 17, 1830, at the age of 47.

While Bolívar is Venezuelan by birth, by the end of his life he likely had more ties to Colombia. His body was initially laid to rest at the Cathedral Basilica of Santa Marta. Twelve years later, Paez secured the repatriation of his remains to Venezuela and they were paraded through Caracas and interred alongside his wife and parents. His body was later moved to the National Pantheon in 1876. His physical heart, however, remained in Santa Marta.

His body was exhumed yet again in 2010, when the socialist leader of Venezuela, Hugo Chávez, maintained that Bolívar had died not from tuberculosis but rather from poisoning at the hands of ”New Granada traitors”. The DNA tests that were run on his bones did not give definite credence to the claims of Chávez, but this incident highlights how impactful the complicated legacy of Bolívar remained more than a century later.

His undeniable legacy extends not only to the six modern countries that claim him as their Liberator. Inexplicably, there are portions of both U.S. states that I have lived in that bear a remembrance of his name. Texas has the Bolivar Peninsula in Galveston County, and Mississippi has a county in the north delta region named Bolivar County. Despite my best efforts, I have not been able to trace the original etiology of why either of these places were named after Bolívar.

The story of Simón Bolívar is as nuanced and complicated as the man himself. Many men in a similar station might have remained seated in the lap of affluence and enjoyed all the privileges that an oppressively wealthy life can afford. Rather, a succession of events ignited the volcanic fires in this man’s eyes as he marched onwards towards his dream of a united South America. While the dream ultimately fell short of its glory, it can never be stated that the man did. At least for me, among conversations of the greatest conquerors in military history, as the names of Alexander, Caesar, and Napoleon are mentioned, forget not Simón Bolívar, American Liberator.

Written by Cal Wilkerson