I recently finished Jack Hurst’s biography Nathan Bedford Forrest, I debated on even approaching perhaps the most controversial General in the American Civil War through a post due to the complicated nature of his legacy. The more I thought about it, the more I wanted to at least attempt it though. He looms large in what I would define as “Civil War Memory”, in a lot of ways is an incarnation of the conflict itself. I actually live in a county that is named after him as well, there is a portrait of him in our County Courthouse and he consistently ranks at the top of many Civil War enthusiast’s favorite generals even today. Shelby Foote who I admire, wrote glowingly of his exploits during the war in his 3-volume trilogy as well. In this post my goal is to approach him as a balanced modern reader of the Civil War.

Nathan Bedford Forrest didn’t leave us much by way of contextualizing him historically, as in he did not leave any memoirs like many others (Grant, Sherman, Longstreet, Chamberlain, etc.). He was primarily active in the Western Theater, an often overlooked yet pivotal region in the Civil War. The lack of personal writings or reflections from Forrest himself has created a kind of vacuum, allowing his image to be shaped largely by historians, admirers, and detractors alike. Unlike generals like Ulysses S. Grant, whose thoughts and strategies we can clearly interpret through their own words, Forrest exists as a figure whose legacy is defined more by the actions others ascribe to him than by any firsthand account of his own motivations or reflections.

This absence of material gives rise to a curious phenomenon: Forrest becomes a kind of blank canvas onto which people project their own interpretations—whether as a brilliant and unconventional military mind or as a symbol of the South’s darker aspects. He was undeniably effective in his role as a cavalry commander, executing daring raids and outmaneuvering Union forces with an instinctive understanding of warfare, but his controversial post-war actions and role in the slave trade further complicate the narrative. This leaves modern readers and historians to piece together who Forrest truly was, often resulting in highly polarized views of his legacy.

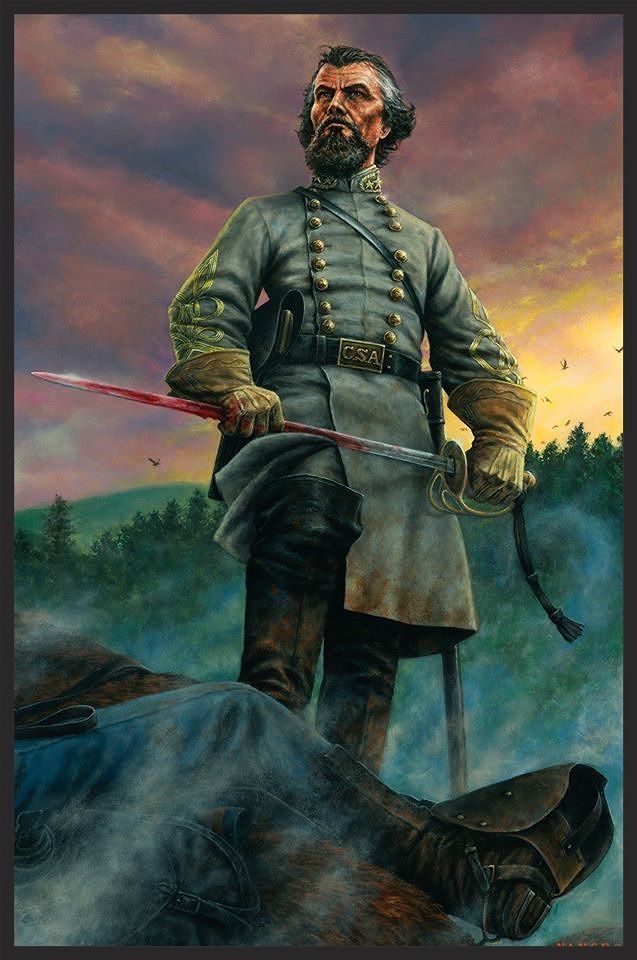

To begin with, Nathan Bedford Forrest was known as the “Wizard of the Saddle”, he was the only soldier in either army to rise from the rank of private to Lieutenant General. He killed thirty Union soldiers in hand to hand combat and had twenty-nine horses shot out from under him. General William T. Sherman said of him, “That devil Forrest must be hunted down and killed if it costs 10,000 men and bankrupts the treasury.” Forrest was feared by the enemy and his men alike, he would personally assault or shoot at soldiers that retreated from battle “Chalmers recalled that Forrest jumped down off his horse, grabbed the frightened trooper, threw him to the ground, and then dragged him to the side of the road, where he began whipping him with a piece of brush. Then, turning him toward the gunfire, he said ‘Now, God damn you, you got back there and fight. You might as well get killed there as here, for if you ever run away again you’ll not get off so easy.’” Forrest is quoted famously, “War means fightin’ and fightin’ means killin’.” He was an imposing man physically for the time period weighing 180 pounds and coming in at six foot one and half inches when the average man of that time period dwarfed in comparison at five foot seven and weighing 140 pounds. So as a calvary man, Forrest was frightening on horseback with saber drawn paired his infamous fiery temper.

Forrest began life on what would be considered the frontier of America, in Chapel Hill, Tennessee in 1821. Until his father’s death in 1837, they lived in Marshall County, Tennessee then moved to Northern Mississippi close to Hernando. At 16 he became head of his household, two of his eight brothers and all three of his sisters died of typhoid fever. There’s a story about Nathan Bedford around that age that I found to be telling of his future, one night his mother Miriam Forrest was coming home through the North Mississippi wilderness with a basket of baby chickens given to her by their nearest neighbor (ten country miles away), getting close to home she was pursued by a panther. The panther attacked, maimed the horse and wanted the chickens which Mrs. Forrest refused to surrender. She was wounded severely by the panther. After young Nathan tended to her wounds he pursued the panther late into the night with his dogs, treed it and vowed to his mother, “Mother, I am going to kill that beast if it stays on earth.” He returned at 9 A.M. the following morning with the animals scalp and ears.

Forrest’s uncle, Jonathan Forrest, had gotten into a business dispute with members of a local gang in Hernando. The gang was known for being violent and lawless. During the conflict, Jonathan was killed by members of this group. Upon hearing the news, Nathan Bedford Forrest, known for his temper and strong sense of loyalty to family, sought revenge. Forrest tracked down the men responsible for his uncle’s death and, confronted them in a saloon. In a violent altercation, Forrest killed two of the men, by shooting them with a shotgun and wounded two others. This event enhanced Forrest’s reputation as a man not to be trifled with. His ability to take swift, brutal action and his willingness to resort to violence when wronged became part of the legend that followed him throughout his life, especially in his later military career. The story reflects both his fierce loyalty to family and the frontier-style justice that was not uncommon in the rural South during the mid-19th century. The author makes a point in the “Frontier” section of his biography about this way of dealing with problems.

By the time the Civil War began, Nathan Bedford Forrest had established himself as a wealthy and successful businessman, in Memphis, Tennessee. While he dabbled in land speculation, cotton, and horse trading, it was his role as a slave trader that significantly contributed to his fortune and has since become a focal point of controversy in his legacy. Forrest’s slave trading business, which he ran in the 1850s, was one of the largest in the Memphis area. He operated a bustling slave market, buying and selling enslaved people in an era when the cotton economy created a high demand for forced labor.

As we approach this first controversial element of Nathan Bedford Forrest’s life, specifically his pre-war business as a slave trader, it’s important to recognize the complexity of the historical debate surrounding his role. Forrest’s involvement in the slave trade has long been a point of contention, and over the years, admirers and detractors have offered starkly different interpretations of his actions. Jack Hurst, in his biography of Forrest, acknowledges that Forrest was indeed a slave broker, but frames him as a pragmatist, driven by the economic realities of the antebellum South. According to Hurst, Forrest’s involvement in the slave trade was less ideological and more about taking advantage of a lucrative industry that, at the time, was not only legal but widely accepted in the Southern economy.

Defenders of Forrest tend to emphasize his relatively “decent” treatment of the enslaved people he trafficked, suggesting that he was more humane than many other slave traders. It is argued that Forrest allowed some enslaved individuals to earn wages and reportedly offered freedom to a few, an act that was unusual for someone in his line of work. Furthermore, there are claims that Forrest did not actively separate families during sales, which defenders argue speaks to a level of compassion not typically associated with slave traders. These arguments position Forrest as someone who, despite engaging in the abhorrent practice of slavery, conducted his business with a certain level of restraint and humanity. Jack Hurst seems to accept, at least in part, that Forrest was motivated by financial pragmatism rather than overt cruelty, noting that his business dealings were seen as a practical way to earn significant wealth.

However, detractors counter that these arguments do little to absolve Forrest of his role in perpetuating the brutal and dehumanizing system of slavery. While some might argue that he treated the enslaved with relative “decency,” critics point out that any involvement in the buying and selling of human beings cannot be softened by claims of moderation. The very nature of slavery, with its inherent violence, separation of families, and denial of basic human rights, means that Forrest’s participation in the trade, regardless of his personal approach, was inextricably linked to a system of cruelty. Historians also question the validity of some of these claims, noting that records of Forrest’s supposed leniency are often based on anecdotal evidence rather than verifiable fact.

In the end, while Forrest’s defenders focus on his business acumen and attempt to highlight differences in how he treated enslaved people, the larger truth is that his wealth and success were built upon the exploitation and suffering of others. Jack Hurst himself, while portraying Forrest as a man of his time, does not shy away from acknowledging the moral ambiguity of Forrest’s involvement in the slave trade. Ultimately, the debate over Forrest’s actions reflects a broader struggle to reconcile his legacy as both a brilliant military mind and a man deeply enmeshed in one of the darkest institutions in American history.

My personal take on the this first controversial element of Nathan Bedford Forrest is that based on his explosive temper, ruthless approach to settling problems, proclivity to violence, I find it hard to believe that he would be more lenient than the average slave trader at the time and I expect that years in that business more than likely made him pretty callused regarding whether or not to separate families, I expect he didn’t care that much which it came down to the bottom line, i.e. him being a “pragmatist”. So certainly, he was a man of his time in that business, I think it’s more of stretch to imagine him as merciful.

Nathan Bedford Forrest’s military career is one of the most distinctive of any Civil War general, largely due to his unconventional rise through the ranks and his unorthodox but highly effective tactics. Drawing from Jack Hurst’s biography, we can trace Forrest’s transition from a private citizen with no formal military training to a cavalry general who became a terror to Union forces in the Western Theater.

Forrest began the Civil War as a private citizen and planter, but quickly leveraged his wealth and connections to raise a cavalry regiment. What makes his story particularly remarkable is that he entered the Confederate Army as a private but rapidly ascended to command, with no formal military background. Unlike many Confederate generals who were West Point graduates or career military men, Forrest was a self-taught soldier. He personally financed the recruitment and equipping of a cavalry battalion, which later became known as Forrest’s Cavalry. By 1862, he had already been promoted to brigadier general, a testament to his natural leadership and tactical ingenuity.

What Forrest lacked in formal training, he made up for with instinct and an almost preternatural understanding of mobile warfare. He excelled in using cavalry not just as a screening or reconnaissance force, but as an aggressive, raiding unit that struck deep into enemy territory, disrupting Union supply lines and communications. His ability to move quickly and strike decisively gave him an edge, particularly in the expansive and often loosely defended Western Theater.

Nathan Bedford Forrest’s role at Fort Donelson and Fort Henry in early 1862 marked one of the first significant tests of his leadership and character during the Civil War. Fort Henry fell to Ulysses S. Grant’s forces on February 6, 1862, largely due to inadequate defenses and a powerful Union naval bombardment. Forrest and his cavalry were involved in the Confederate defense of the surrounding areas, but the fort itself was quickly overtaken. His participation at Fort Henry was minor compared to what would unfold at Fort Donelson, where his boldness and refusal to surrender became defining traits of his wartime legacy.

At Fort Donelson, after Grant’s forces had surrounded the Confederates, the situation quickly deteriorated for the Southern defenders. On February 16, 1862, facing overwhelming odds, the Confederate leadership began negotiating terms of surrender. Forrest, however, vehemently opposed surrendering. As the Confederate generals, including Simon Bolivar Buckner, prepared to capitulate, Forrest’s defiance stood out. He famously declared, “I did not come here to surrender my command,” and resolved to lead his men out of the encirclement rather than face capture.

That night, Forrest and about 700 of his men made a daring escape through icy, flooded backwaters, cutting through Union lines under cover of darkness. His decision to refuse surrender at Fort Donelson was one of the early moments that forged his reputation as a bold and unyielding leader. Jack Hurst notes that Forrest’s escape, while not a decisive moment in the larger battle, exemplified his unwillingness to accept defeat and his preference for aggressive action, no matter the circumstances. Grant’s victory at Fort Donelson was a major Union triumph, but Forrest’s refusal to surrender marked the beginning of his rise as a Confederate icon of resistance.

Forrest’s cavalry first came into prominence during the Battle of Shiloh in April 1862, a battle that nearly became a disaster for the Confederate forces under General Albert Sidney Johnston and P.G.T. Beauregard. Forrest was involved in the fighting on the second day, but his most notable contribution came immediately after the battle at the engagement known as Fallen Timbers. As the Confederate army retreated from Shiloh, Forrest led his cavalry in a rear-guard action to fend off Union forces. During the engagement, Forrest found himself deep behind enemy lines, where he famously charged into a Union brigade single-handedly and suffered a gunshot wound to the back. A quote from one of his soldiers describing Forrest in combat, “it bore (Forrest’s face) a striking resemblance to a painted Indian warrior’s, and his eyes, usually mild in their expression, were blazing with the intense glare of a panther’s springing upon its prey.” This moment showcased his fearless nature and earned him a reputation for personal bravery, something that would become legendary throughout the war.

Forrest’s command soon became synonymous with the kind of bold, rapid strikes that typified cavalry warfare at its best. His tactics were honed through a series of raids, where he used his cavalry’s mobility to outmaneuver larger Union forces. His raid on Murfreesboro in 1862 is a prime example of his genius. Forrest launched a surprise attack on Union garrisons, capturing significant numbers of soldiers, destroying supplies, and wreaking havoc on Union operations. His success here was not just due to his speed but also his ability to gather intelligence, improvise in battle, and instill fear in the enemy.

Forrest’s raids throughout Tennessee, Mississippi, and Kentucky were a constant thorn in the side of Union forces. His destruction of Union supply lines and railroads disrupted the larger strategic goals of Union generals like Ulysses S. Grant. Forrest understood that in a war of attrition, such disruptions could have an outsized effect on the larger strategic picture. His ability to wage asymmetrical warfare made him one of the Confederacy’s most effective generals in the West.

One of the most striking elements of Forrest’s career, which Hurst highlights, was his personal involvement in combat, “Forrest himself picked off a Federal sniper in a tree with Maynard rifle hastily borrowed from an enlisted man.” Unlike many generals who remained far from the front lines, Forrest frequently led from the front. His hand-to-hand combat prowess became the stuff of legend, with multiple accounts of Forrest personally killing Union soldiers in close-quarters combat, “There in the road was General Forrest with his escort, and a few of the advance-guard of the Forrest brigade, in a hand to hand fight… with Federals enough… to have pulled them from their horses… Forrest is reported to have personally killed three of them in the fight in the road.” He famously declared that he had personally killed over 30 men in battle, and whether or not the number is exaggerated, the fact remains that he was a hands-on leader who inspired fear and loyalty in equal measure.

Forrest’s bravery was evident when he was shot by one of his own soldiers in 1863. The incident occurred during a confrontation with one of his men, Andrew Gould, who had questioned Forrest’s authority. Forrest, never one to shy away from a fight, reportedly struck Gould, who responded by shooting the general in the hip. Forrest, despite being severely wounded, pursued Gould and killed him with his knife famously quoted for saying “I’ll be damned if I don’t kill him, and I’ll be damned if he kills me.” This incident further contributed to Forrest’s aura of invincibility and ruthlessness. It also speaks to his temperament—Forrest was not known for patience or diplomacy, traits that both helped and hurt him in his military career.

At Brice’s Crossroads on June 10, 1864, Nathan Bedford Forrest demonstrated the full extent of his military ingenuity, outmaneuvering a numerically superior Union force with remarkable tactical skill. Jack Hurst, in his biography of Forrest, highlights this battle as one of Forrest’s most brilliant victories, showcasing his ability to exploit terrain, speed, and psychological warfare. Forrest’s strategy at Brice’s Crossroads was to lure Union General Samuel Sturgis’ 8,500-strong army into a narrow and swampy area, where their numbers would be less of an advantage. Forrest’s smaller force of about 3,500 cavalrymen attacked with a precision and aggression that overwhelmed the Union troops, causing chaos in their ranks. Hurst notes that Forrest understood the importance of striking quickly and decisively, famously saying before the battle, “We’ll whip ‘em on our side of the river, and then we’ll whip ‘em on the other side.”

Hurst views Brice’s Crossroads as the epitome of Forrest’s unconventional warfare. Rather than adhering to traditional military doctrine, Forrest relied on his deep understanding of terrain and his troops’ mobility to turn the tide of battle. Hurst emphasizes how Forrest’s ability to inspire confidence in his men and strike fear in his enemies played a crucial role. By outflanking the Union forces and attacking their supply lines, Forrest not only forced them into a retreat but also inflicted heavy losses—around 2,240 Union casualties compared to his 492. This victory solidified Forrest’s reputation as a tactical genius, and Hurst suggests that it was battles like Brice’s Crossroads that cemented Forrest’s mythos in Civil War memory as a commander who could do more with less, repeatedly defying the odds through sheer audacity and strategic insight.

Forrest’s career was not without controversy, particularly in regard to his involvement, or lack thereof, in some of the key battles in the Western Theater, specifically at Chattanooga and Nashville. At the Battle of Chattanooga in November 1863, Forrest clashed with Confederate General Braxton Bragg. Forrest was increasingly frustrated with Bragg’s cautious and often indecisive leadership. After the Confederate defeat at Chattanooga, Forrest openly criticized Bragg, reportedly telling him, “You have played the part of a damned scoundrel.” The tensions between the two men became so great that Forrest was reassigned to a more independent command, which some argue was actually to his advantage, as he performed better when given autonomy. On a side note to this feud with Bragg, Forrest also was in line for a duel with another famous Mississippian of the Confederacy, General Van Dorn but before the two could settle the matter, Van Dorn was assassinated by the husband of a woman he was having an affair with.

The Battle of Fort Pillow, fought on April 12, 1864, is one of the most controversial moments in Nathan Bedford Forrest’s military career, particularly because of the brutal aftermath. Fort Pillow, located on the Mississippi River in Tennessee, was held by a mixed Union garrison of roughly 600 troops, including white Southern Unionists and African American soldiers from the U.S. Colored Troops. Forrest led a Confederate cavalry force to capture the fort as part of his wider campaign to disrupt Union operations along the river. Forrest’s troops surrounded the fort and launched several assaults on the defenses. After several hours of fighting, and with the Union forces trapped inside, Forrest demanded surrender. Union Major William Bradford refused the offer, but after further Confederate attacks, the defenses collapsed. Confederate troops overwhelmed the Union forces, and soon after, a massacre ensued.

This is where the controversy begins. Many Union soldiers, particularly African American troops, were killed in what has been described as a massacre after they had surrendered or were attempting to surrender. Confederate forces fired on Union soldiers as they fled toward the river, killing many of them. The total number of Union casualties was around 300, with a high percentage of African American troops killed compared to their white counterparts. This led to widespread outrage in the North and accusations that Forrest and his men committed a war crime, specifically targeting Black soldiers who were attempting to surrender.

Forrest’s defenders argue that the situation was more complicated. Some claim that the Union troops did not properly surrender and that fighting continued after the fort fell. According to this view, the chaos of the battle, compounded by the racial tension between Confederate forces and the Black Union soldiers, not to mention and maybe even worse in the eyes of the attackers, Unionist Tennessee soldiers, led to uncontrolled violence rather than a premeditated massacre. Defenders also point out that Forrest issued orders to stop the killing once it became apparent that the Union forces had been defeated, and that reports of the massacre were exaggerated by Union sources for propaganda purposes. They argue that Union forces were actively resisting, and many of the deaths occurred in the heat of battle rather than after a formal surrender.

In his biography of Forrest, Jack Hurst acknowledges that Forrest’s defenders have often used these arguments to portray him in a more favorable light. However, Hurst also notes that the presence of numerous reports from both Union and Confederate witnesses supports the view that a massacre did occur, even if the extent of Forrest’s direct involvement remains disputed.

Critics, particularly in the North during and after the war, point to Fort Pillow as evidence of Forrest’s cruelty and his willingness to allow or even encourage the massacre of Black troops. The high casualty rate among African American soldiers, especially compared to the white soldiers at Fort Pillow, is often cited as proof of racial violence. Testimonies from survivors and Northern newspapers, as well as official Union reports, emphasize that Black soldiers were specifically targeted and killed after trying to surrender, which violated the rules of war.

Forrest’s role in the massacre is also complicated by the post-battle reports, where he either denied any responsibility or suggested that the Union forces brought the massacre on themselves by refusing to surrender in a timely manner. However, his critics argue that, as the commanding officer, Forrest bore ultimate responsibility for the conduct of his troops and should have done more to control them, especially given the racial dynamics of the situation.

In his biography, Jack Hurst takes a more nuanced view of the Fort Pillow Massacre, acknowledging both sides of the debate. He recognizes that Forrest’s men were indeed guilty of excesses, particularly in their treatment of Black Union soldiers, but he also suggests that the chaotic nature of the battle and the intensity of the fighting played a role in the resulting violence. Hurst does not fully exonerate Forrest but emphasizes that the massacre was not a simple, one-dimensional event of cruelty. Instead, he frames it as a tragic episode that reflected the broader racial and social tensions of the time.

Hurst also critiques the tendency of both Forrest’s defenders and his detractors to simplify the situation. He highlights the fact that, regardless of Forrest’s direct involvement or intentions, the massacre was a deeply troubling event that stained his military career and contributed to his controversial legacy in Civil War memory.

My personal take on this second controversial portion of Forrest’s legacy is similar to Hursts, based on the character of Forrest that we know he was nonetheless a proponent of the normal rules of warfare. He allowed a surrendering Union officer to retain a sword that had been in his family since the War of 1812, he was noted to have treated POWs favorably and provided reasonable rations for them. On the other hand later in life, as he sought reconciliation and promoted a more moderate image, he rarely addressed the incident directly, allowing it to become a point of contention for both his admirers and detractors. In essence, his approach to Fort Pillow was to minimize and deflect responsibility, avoiding an outright defense of the actions but never fully admitting to any wrongdoing. In this way yet again Forrest remains mysterious, if I were a betting man I’d say Forrest didn’t go out of his way to stop the “killin” regardless of if he encouraged it, witnessed it or sanctioned it. I will close my point with Forrest’s quote in Meridian after the surrender of Confederate forces to a reporter that Hurst references, “If you want to know the truth about it, ask any soldier who was there… either one of ours or one of theirs, and if you to believe a lying n*****, then I can’t help you.”

The Battle of Nashville in 1864 was another moment of controversy for Forrest. Serving under General John Bell Hood, Forrest’s cavalry played a key role in the defense of the city. However, the battle resulted in a crushing defeat for the Confederates, with Hood’s army effectively destroyed. Forrest’s role in the battle has been debated—some argue that Forrest did all he could in an impossible situation, while others suggest that his efforts were insufficient in turning the tide. Jack Hurst notes that while Forrest was not responsible for the defeat, his inability to decisively influence the outcome reflected the limitations of cavalry in the face of entrenched infantry and overwhelming Union numbers.

Nathan Bedford Forrest’s military career is filled with moments of brilliance, controversy, and personal involvement in combat that few other generals could claim. From his meteoric rise from private to general, his fearless leadership in battle, and his innovative use of cavalry tactics, Forrest became a figure of awe and fear in the Western Theater. Jack Hurst’s biography provides a nuanced view of Forrest, acknowledging his tactical genius while also pointing out the controversial decisions and personal conflicts that marked his career. Forrest’s legacy as a military leader is complex, shaped by both his undeniable successes on the battlefield and the controversies that surrounded his actions and personality.

Nathan Bedford Forrest’s legacy as a military genius has been shaped by a variety of factors, including a series of influential books, articles, and post-war cultural movements, most notably the Lost Cause ideology. The mythos surrounding Forrest began to take shape soon after the Civil War, with many of his admirers seizing on his remarkable military exploits to elevate him as an iconic Confederate hero. Proponents of Forrest’s military genius, as well as those who have contributed to certain myths about him, were often deeply intertwined with efforts to reframe the war in terms more favorable to the defeated South.

One of the most influential early works was John Allan Wyeth’s 1899 biography, That Devil Forrest, which was among the first to elevate Forrest to a status of near-mythical proportions. Wyeth, a Confederate veteran himself, portrayed Forrest as a tactical genius who could outthink and outfight better-supplied Union forces. The book offered vivid descriptions of Forrest’s battlefield exploits, often emphasizing his courage, daring, and brilliance in using cavalry to disrupt Union supply lines and perform deep raids into enemy territory. Wyeth’s work, while highly readable and engaging, also contributed to the formation of what became known as the “Forrest legend”—the idea that Forrest was an unparalleled military mind whose abilities alone nearly shifted the course of the war. However, Wyeth’s work is now regarded as highly romanticized, often downplaying Forrest’s controversial actions and involvement in slave trading and focusing instead on his battlefield heroics.

Forrest’s post-war reputation became tied to the broader Lost Cause movement, which sought to recast the Confederacy’s defeat in a more noble light. This cultural movement promoted the idea that the South had fought valiantly for “states’ rights” and a way of life, downplaying the centrality of slavery to the conflict. Key figures in this movement, including Edward A. Pollard and Jefferson Davis, looked for Confederate icons to embody their narrative of Southern honor and resilience. Forrest, with his dramatic battlefield successes and his outsider status (having risen from private citizen to general without formal training), became an ideal figure for Lost Cause proponents to rally around.

Forrest’s military career was often presented as a model of Southern ingenuity and grit, contrasting with the supposedly mechanical, industrial might of the Union forces. His image as a “man of the people” who rose through sheer determination and tactical brilliance resonated with Lost Cause ideology, which glorified the Confederacy’s struggle as a heroic but doomed effort. This reimagining of Forrest’s legacy glossed over the more unsavory aspects of his life.

In the 20th century, Forrest’s reputation as a military genius was cemented further by authors like Shelby Foote, whose massive three-volume narrative of the Civil War greatly influenced popular perceptions of the conflict. Foote, who was himself a product of Southern culture, wrote admiringly of Forrest’s abilities, calling him one of the great natural military geniuses of the war. Foote’s work, while more measured than earlier Lost Cause writings, still portrayed Forrest as a heroic and often misunderstood figure, particularly in terms of his military contributions. In his narrative, Foote emphasized Forrest’s tactical prowess, particularly his ability to strike quickly, disrupt Union operations, and lead men in battle. Foote’s writing contributed to the modern-day view of Forrest as one of the most effective commanders in the Civil War, a view shared by many military historians. However, this focus on Forrest’s military accomplishments also contributed to the enduring myth that he was simply a brilliant tactician, with less attention paid to his darker legacies, including his role in the Fort Pillow Massacre and his post-war associations with white supremacist violence.

The development of Nathan Bedford Forrest’s reputation as a military genius, and the associated myths, has been a process deeply influenced by the Lost Cause narrative and works that romanticized his exploits. Early biographies like Wyeth’s and more modern narratives like Shelby Foote’s popularized an image of Forrest that was largely focused on his battlefield prowess, often at the expense of a fuller understanding of his controversial role in the Confederate cause and his post-war activities. While recent works like Jack Hurst’s biography offer a more critical view of Forrest, the image of him as a Confederate hero and tactical genius remains strong in Civil War memory, shaped by decades of selective interpretation.

Nathan Bedford Forrest’s life after the Civil War is a crucial part of understanding his legacy, filled with both his attempts to rebuild financially and his controversial association with the Ku Klux Klan (KKK). While his military career has been widely examined, his post-war actions provide another complex layer to his historical portrayal. Before the war, Forrest was one of the wealthiest men in the South, largely due to his various business ventures, including real estate, slave trading, and cotton plantations. However, the war devastated his finances. By the time the Confederacy collapsed, Forrest had lost the vast majority of his pre-war fortune, which had been tied up in Confederate currency, slaves, and other assets that were devalued or seized after the Union victory. After the war, Forrest tried to revive his financial standing through several business endeavors, but his post-war life was marked by financial struggle. He invested in the Selma, Marion, and Memphis Railroad, hoping to capitalize on the South’s need for transportation rebuilding. However, the railroad venture failed, and Forrest’s lack of formal education and expertise in running large-scale businesses hampered his efforts. In addition to the railroad, he briefly ran a sawmill and invested in a variety of ventures, but none yielded significant profits. By the end of his life, Forrest was in relatively poor financial condition compared to his pre-war wealth, a sharp contrast to his once-prosperous status.

Forrest’s post-war legacy is inextricably tied to the controversy surrounding his alleged involvement with the Ku Klux Klan. The KKK, founded in 1865, initially started as a loosely organized social club in Tennessee but quickly became a paramilitary group using violence and intimidation to oppose Reconstruction and the advancement of freed African Americans.

One of the most debated aspects of Forrest’s post-war life is whether he was the Klan’s first national leader, often referred to as the “Grand Wizard.” Many historians, including Jack Hurst, acknowledge that Forrest likely had a role in the Klan’s early organization, but his level of direct involvement remains contested. Hurst notes that Forrest probably sympathized with the Klan’s goals during Reconstruction, particularly its opposition to federal military occupation and its defense of white Southern supremacy. Some historical accounts claim that Forrest was indeed appointed as Grand Wizard, but there is little conclusive documentary evidence directly linking him to formal leadership of the Klan. Forrest himself denied being the Grand Wizard in testimony given during Congressional hearings investigating the KKK in 1871. He claimed that he had nothing to do with the organization’s violent activities and had even called for it to disband when it became increasingly associated with lawlessness and racial terrorism. Forrest’s defenders argue that he distanced himself from the Klan when its violence escalated beyond what he had envisioned, focusing instead on reconciliation efforts, particularly toward the end of his life.

The argument over Forrest’s involvement in the KKK is part of a broader historiographical debate about his post-war legacy. Some historians and supporters of Forrest argue that the Klan of his era was different from the modern conception of the KKK, which is primarily associated with the racial violence of the 20th century. In the 1860s, the Klan was, in the eyes of some, a reactionary group opposing what they saw as the abuses of Reconstruction, rather than an explicitly terrorist organization. Forrest’s defenders suggest that, while the Klan did engage in violent acts, its goals at the time were more focused on the restoration of white rule in the South, not the systemic, institutionalized racial terrorism that later versions of the Klan would embody.

On the other hand, critics argue that regardless of the Klan’s early intentions, it was responsible for a wave of violence aimed at suppressing Black political and social advancement during Reconstruction. Forrest’s association with the group, however loosely defined, is seen as evidence of his complicity in that violence. Hurst acknowledges this tension, noting that while the Klan may have initially been more of a reactionary political movement, its actions quickly escalated to a level of brutality that cannot be excused. Jack Hurst’s biography continually presents Forrest as a pragmatist who may have used the Klan for his own ends, but also a man who faced the limitations of his own ambitions and the changing nature of post-war Southern society.

My personal take on this third controversial portion of Forrest’s legacy is that he was likely aware of the Klan’s activities and would’ve made a lot of sense on paper, in hindsight and through deductive reasoning to be the leader of it at the beginning. Forrest goes more out of his way to absolve himself from that association more than even the Fort Pillow massacre, he said in a congressional hearing in 1871, “I have never been connected with the Klan. I never was a member of the Klan… I am not connected with it and never have been.” I also believe in private he was sympathetic to the Klan’s goals based on the Union occupation of the South and the changes in the society that were occurring. Yet again, General Forrest is a mystery and leaves that canvas open for argument even over 100 years later.

I want to address an overlooked yet redemptive aspect of Nathan Bedford Forrest: his saving faith. Forrest’s religious conversion toward the end of his life is a significant aspect of his post-war legacy. After years of violence, controversy, and involvement in the Civil War and possibly the Ku Klux Klan, Forrest underwent a personal transformation that many interpret as genuine repentance.

In 1875, Forrest made a public profession of faith, joining the Cumberland Presbyterian Church. He was baptized and began to speak about his newfound beliefs in Christian gatherings. Forrest expressed deep regret for his past actions, particularly his role in the institution of slavery, saying: “I was a sinner, and I needed forgiveness. I had wronged both the Black man and the white. But, I turned to God in repentance.”He was reported to have spoken openly about seeking forgiveness for the wrongs he had committed, asking both God and those he had harmed to pardon him. Forrest’s conversion did not go unnoticed, and some accounts suggest he sought to reconcile his past with his faith, making amends in the final years of his life.

One of the most poignant moments came in 1877, when Forrest addressed a group of Black Southerners at a meeting of the Independent Order of Pole-Bearers, a forerunner to the NAACP. In a speech that would have been unthinkable just years earlier, Forrest said: “I came here with the jeers of some white people, who think that I am doing wrong. I believe I can exert some influence, and do much to assist the people in strengthening fraternal relations, and shall do all in my power to bring about peace.” His religious conversion was a major turning point in how Forrest sought to redefine himself, and for Christians, his story reflects the power of redemption. As difficult as it might be to reconcile his earlier life with his later transformation, Forrest’s repentance stands as a testament to the belief that no person is beyond the reach of God’s grace. My personal opinion on this aspect of Nathan Bedford Forrest is that he did find true saving faith in Jesus Christ, it is evidenced by his words and deeds.

Nathan Bedford Forrest passed away on October 29, 1877, in Memphis, Tennessee, at the age of 56. His health had steadily declined due to complications from diabetes, and he spent his final days in relative quiet, reflecting on his past and embracing the faith he had found late in life. As Jack Hurst notes in his biography, Forrest’s bedside reflected this duality of his life: on one side lay the Bible, symbolizing his conversion to Christianity and repentance, and on the other, A History of Forrest and His Men, a testament to his indelible connection to his Civil War exploits. Forrest’s final words, spoken softly, encapsulated his sense of spiritual readiness: “I am tired and ready to go home.” These words convey a deep sense of peace and acceptance, as he believed he had made amends with God and was prepared for the afterlife. His death was a marked contrast to the turbulent and often violent life he had led. For many, his passing highlighted the complexities of his legacy—a man who sought forgiveness and redemption after a life that had left an indelible mark on American history.

Nathan Bedford Forrest remains one of the most controversial figures of the American Civil War, embodying both the brutality of the era and the complexities of the individuals who lived through it. His rise from humble beginnings to become a feared and admired cavalry commander speaks to his undeniable military genius, yet his pre-war involvement in the slave trade and his post-war association with the Ku Klux Klan cast long shadows over his legacy. Historians, including Jack Hurst, have tried to strike a balance between recognizing his tactical brilliance and confronting the darker aspects of his life, particularly his role at Fort Pillow and his involvement in a system that profited from human suffering. Forrest, like the war itself, is difficult to categorize neatly—he was a man of contradictions, capable of both calculated violence and deep personal loyalty.

Yet Forrest’s later years, marked by his conversion to Christianity and his open repentance, complicate his legacy further. His public renunciation of his past, alongside his efforts to promote reconciliation and peace, suggest a man who sought redemption after years of division and conflict. While his military feats have propelled him into the pantheon of celebrated Confederate leaders, his personal transformation near the end of his life offers another dimension to his story. Forrest stands as a representation of the Civil War’s enduring complexity—he is both a product of his time and an individual whose life underscores the difficult, often uncomfortable truths about war, race, and reconciliation in American history. As controversial as his legacy remains, Forrest’s story forces us to confront the contradictions and consequences of that turbulent period.

Appendix: List of Forrest’s service record in Civil War.

1. Fort Donelson (February 11–16, 1862) Led cavalry forces, famously refused to surrender, and escaped with 700 men.

2. Battle of Shiloh (April 6–7, 1862) Commanded cavalry on the Confederate right flank, where he conducted reconnaissance and rear-guard actions. Wounded during a counterattack at Fallen Timbers on April 8.

3. First Battle of Murfreesboro (July 13, 1862) Led a surprise cavalry raid against a Union garrison, securing a Confederate victory and earning recognition for his tactical acumen.

4. Kentucky Raid (July–August 1862) A series of raids across Middle Tennessee and into Kentucky, capturing supplies and causing significant disruption to Union forces.

5. Battle of Parker’s Cross Roads (December 31, 1862) Attacked Union forces but was forced to withdraw after being caught between two columns.

6. Battle of Thompson’s Station (March 5, 1863) Captured a Union brigade in a successful cavalry action, showing his continued effectiveness in mounted warfare.

7. Tullahoma Campaign (June 24–July 3, 1863) Provided rear-guard actions during the Confederate retreat from Middle Tennessee.

8. Chickamauga Campaign (September 18–20, 1863) Played a key role in capturing Union positions during the Battle of Chickamauga.

9. Raid on Memphis (August 21, 1864) A daring raid on Union-held Memphis, nearly capturing several high-ranking officers.

10. Battle of Brice’s Crossroads (June 10, 1864) One of Forrest’s most famous victories, where he decisively defeated a much larger Union force using superior tactics.

11. Battle of Tupelo (July 14–15, 1864) Fought against Union forces under General A.J. Smith but was forced to withdraw after sustaining heavy casualties.

12. Raid on Johnsonville (November 4–5, 1864) Destroyed a major Union supply depot along the Tennessee River, causing millions of dollars in damage.

13. Nashville Campaign (November–December 1864) Participated in delaying actions during Hood’s ill-fated campaign, notably in the defense at the Battle of Franklin and covering the retreat after the Battle of Nashville.

14. Selma (April 2, 1865) Commanded Confederate forces during the defense of Selma, Alabama, against a Union cavalry attack led by General James H. Wilson. Captured in the aftermath but soon paroled.