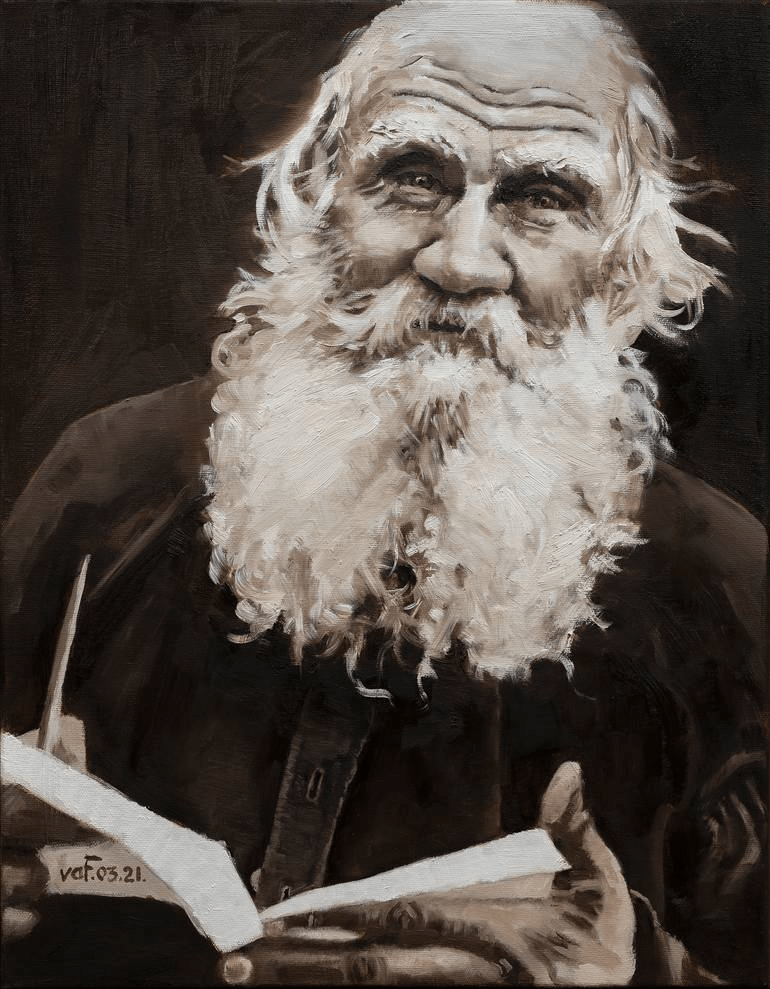

As with so many other works that I have reviewed thus far, A Confession by Leo Tolstoy, published in 1882, is a brief autobiographical story of the author’s mid-life existential crisis. This short work teases out the theodicy from the perspective of a melancholic 50-year-old post-academic success and fame. Typical of others after the thrills of notoriety and fortune have worn off, Tolstoy began to plummet into an abyss of self-doubt and nihilism. “It was impossible to stop, impossible to go back, and impossible to close my eyes or avoid seeing that there was nothing ahead but suffering and real death – complete annihilation.”

Tolstoy’s despair drove him to the brink of suicide, stating that some irresistible power was impelling him to rid himself of his life and that the thought of self-destruction came to him as naturally as thoughts of self-improvement had come formerly. Not only this, but he also began to doubt everything that he had ever done in his five decades of life, stating: “I could give no reasonable meaning to any single action, or to my whole life”.

His despondency was multifactorial, but it consisted of the fear or reality of sickness and death coming to those closest to him, so that “nothing will remain but stench and worms.” Additionally, he suspected [albeit incorrectly] that with time his works and affairs “will be forgotten”. The future and inevitable termination of his existence led him to conclude that there is no sense in making any effort to go on existing.

Tolstoy relates the will to existence as synonymous to being drunk. “One can only live while one is intoxicated with life; as soon as one is sober it is impossible not to see that it is all a mere fraud and a stupid fraud!” Not ready concede that this condition of despair is natural to humanity, he set out on a quest to find an explanation for the problem of despair in all branches of knowledge available to him, “sought as a perishing man seeks for safety – and found nothing”.

Along his frantic journey, Tolstoy initially sought refuge in what was most comfortable to him at the time – the empirical sciences. He was gravely disappointed with what he discovered, noting that the sciences “had plainly acknowledged that the very thing which made me despair – namely the senselessness of life – is the one indubitable thing man can know.”

Tolstoy only wanted an answer to “the question without answering which one cannot live: Is there any meaning in my life that the inevitable death awaiting me does not destroy?”

His scientific inquiries are almost amusing in their ineptitude to give him the comfort which he so desperately seeks. “I received an innumerable quantity of exact replies concerning matters about which I had not asked”. These included “the chemical constituents of stars, the movement of the sun towards the constellation Hercules, the origins of the species of man, the forms of infinitely minute imponderable particles of ether”. The reply that he received from his inquiry was derisory:

“You are what you call your life; you are a transitory, causal cohesion of particles. The mutual interactions and changes of these particles produce in you what you call your life. That cohesion will last some time; afterwards this interaction will cease, and what you call life will cease, and so will all of your questions. You are an accidentally united little lump of something. That little lump ferments. The little lump calls that fermenting its ‘life’. The lump will disintegrate, and there will be an end of the fermenting and of all the questions.”

That the meaning of his life was a fragment of the infinite destroyed its every possible meaning. Tolstoy was not satisfied, and he looked elsewhere for answers. He then decided to look amongst his peers and realized that there were essentially only four types of people in his circle of friends as relates to the “terrible position in which we are all placed”. One can choose ignorance, epicureanism, strength and energy, or weakness.

Despite its negative connotation, Ignorance [consisting in not knowing or understanding] is not an inherently terrible position to take. If one is oblivious to the fact that “life is an evil and an absurdity,” then life becomes bearable. This strategy would not work for Tolstoy because his very dilemma was that he was not ignorant of his impending demise and could not retroactively feign ignorance. “From them I had nothing to learn – one cannot cease to know what one does know.”

Epicureanism seemed a reasonable alternative: knowing the hopelessness of life, making use of the advantages it affords meanwhile is not the worst path to take. Tolstoy took a moral exception to this position on the grounds that living the epicurean lifestyle requires wealth and privilege that the masses do not have access to and does not solve the issue except for the select few who can afford it.

Strength and Energy is a bleak solution to his dilemma. It consisted of recognizing that life is an evil and an absurdity, and then destroying life. He considered suicide to be the most honest response to the inevitability of death and the assumption that God does not exist. Tolstoy admits that he was unable to follow this path due to his own cowardice.

The final path was Weakness, the one that he was currently taking at the time of his writing. “It consists of seeing the truth of the situation, and yet clinging to life, knowing in advance that nothing can come of it.” It was precisely this state of weakness that he was living in at the time that drove him to the point of madness. He was incapable of returning to Ignorance, abhorrent of Epicureanism, too cowardly for Strength and Energy.

Tolstoy then decided to look towards the possible existence of God. He was dissatisfied with the classic Cosmological Argument and instead turned to the great Russian mysticism. “I must seek this meaning not among those who have lost it and wish to kill themselves, but among those milliards of the past and the present who make life and support the burden of their own lives.” The anomalous way in which these individuals live “do not fit into my divisions, and that I could not class them as not understanding the question, for they themselves state it, and reply to it with extraordinary clearness.”

Tolstoy is referring primarily to the Russian peasants who have an irrational faith in God that cannot be grasped with reason. His definition of faith is “a knowledge of the meaning of human life in consequence of which man does not destroy himself but lives.. it is the strength of life.” He goes on to say that if a man lives he believes in something. The entire aim of man in life is salvation, and to do this he must live godly and “renounce all the pleasures of life, must labor, humble himself, suffer, and be merciful.”

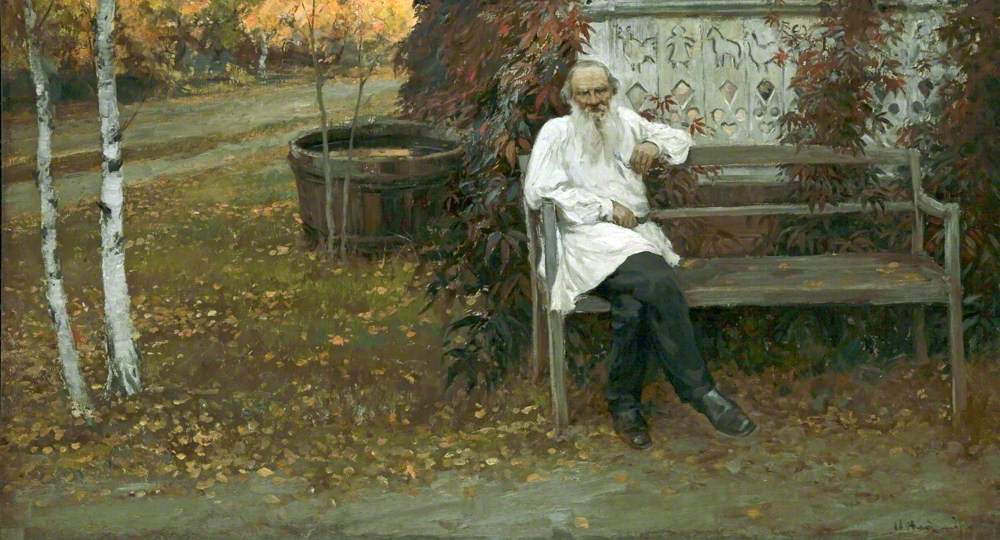

His deep convictions as to the truth of this proposition led Tolstoy to make an extreme departure from his affluent life in an attempt to emulate the Russian peasantry in their mystical Christian faith. His criticism of the Russian Orthodox establishment church led to his ultimate excommunication in 1901. He subsequently renounced his estate and writings and attempted to live as a poor wandering ascetic. While his radical departure from convention led to wide influence and several nominations for the Nobel Peace Prize and Nobel Prize in Literature, it certainly did not engender him to his wife and family who saw this essentially as abandonment.

Tolstoy defends himself by saying that “I had been led by indubitable experience to the conviction that only these propositions presented by faith give life a meaning.” He laid to rest his endless pursuit of certainty. “I know that the explanation of everything, like the commencement of everything, must be concealed in infinity.” He recognized that this was so “not because the demands of my reason are wrong, but because I recognize the limits of my intellect.”

Ultimately, Tolstoy found the peace to persist and a reason for existence that gave meaning to his life. He can be seen in a way almost as the Eastern mystical counterpart to Kierkegaard’s leap of faith. Both were disillusioned by the comfortable lives that they had led and the notoriety they had garnered and chose a radical departure from societal conventions to a life that they could recognize as honest and real. There is so much more left for me to explore in the life and works of Tolstoy, and this work is certainly not the most natural starting point for such an endeavor. Nevertheless, I am enamored by the thoroughly conscientious and methodical approach to despair displayed by Tolstoy in this seminal work and I will undoubtedly return to the works of this towering figure of Christian existentialism.

Link to purchase: https://www.amazon.com/Confession-Lev-Tolstoy/dp/B09GJV1TNV/ref=tmm_hrd_swatch_0?_encoding=UTF8&qid=1699386593&sr=8-2-spons

Written by Cal Wilkerson