“Creation is a nightmare spectacular taking place on a planet that has been soaked for hundreds of millions of years in the blood of all its creatures. The soberest conclusion that we could make about what has actually been taking place on the planet for about three billion years is that it is being turned into a vast pit of fertilizer”.

I first read Denial of Death in 2017-2018 while in Malawi, and to be honest, I have no idea what the inspiration for the read was. I am sure that I was referred to it by some other book that I was reading at the time, but it still baffles me to this day why I ever picked up this book. What I read while in Malawi so shocked and horrified me that I literally postponed this blog post for 4 years. What could I even say concerning things I was not yet ready to process? In fall 2020 I decided to pick up this 1974 Pulitzer Prize winning book for a second read and finally lay it to rest.

At face value, this book is simply Ernest Becker’s attempt at expounding on the work of Otto Rank and Norman Brown’s interpretation of Sigmund Freud’s interpretation of Soren Kierkegaard. That is my tongue in cheek way of saying it seems at first glance to be yet another book on Western psychology and sociological anthropology. In many ways, this is exactly what this book is; however, this book struck a nerve like no other work has before. It was the simple retelling of the ideas of long-dead white men whom the general public probably has little to no knowledge of, but the execution was so unsettling and disturbing as to not leave the reader with one ounce of security about his place in the world.

“Man is a creator with a mind that soars out to speculate about atoms and infinity, who can place himself imaginatively at a point in space and contemplate bemusedly his own planet. This immense expansion, this dexterity, this ethereality, this self-consciousness gives to man literally the status of a small god in nature… yet, at the same time, man is a worm and food for worms”.

Becker certainly does not spare the reader this reminder. He encourages us to remember that all human beings, despite the symbolic significance they may place on their own lives, were born between urine and feces. He also reminds us that one of the most intimate acts humans can perform, the kiss, is done with lips that are the beginning of the alimentary canal leading to the ultimate expulsion of feces and flatulence from the anus. Such talk has no place in civilized society, but that is precisely the point. Mentally dwelling on such things brings our death anxiety to the forefront, revealing that we are primarily physical beings with an expiration date rather than symbolic beings engaged in some elaborate immortality project.

“The real world is simply too terrible to admit; it tells man that he is a small, trembling animal who will someday decay and die. Culture changes all of this, makes man seem important, vital to the universe, immortal in some ways.”

The premise of the book rests in the idea that the core anxiety of man is his fear of the inevitability of death, and that all human civilization is an elaborate, symbolic defense mechanism against that knowledge. Becker sees humans as existing in two separate realms – a physical self and a symbolic self – and that the symbolic self allows humans to transcend their physical mortality through the act of heroism. This is little more than a desperate ploy; heroism is simply the shifting of our focus away from the animal towards the symbolic. Becker calls this focus on the symbolic an individual’s “causa sui” project – essentially an individual’s attempt to achieve immortality by assuring himself or herself that symbolism can transcend personal physical decay. As long as an individual fulfills their unique causa sui project, they will transcend the physical and become part of something symbolically eternal – which bestows a sense of purpose and meaning to individuals.

Of course, society cannot allow this thought to come to the fore, lest we all descend into collective neurosis. So instead of being revealed as the naked worms that we are, only concerned with three square meals a day and a constant obsession with biological procreation, society transforms us into something else entirely through the causa sui project. We become fathers and mothers, sons and daughters, brothers and sisters, lovers, teachers, patriots, plumbers, chefs, doctors, lawyers, engineers, adventurers, authors, musicians, NASCAR fans, and faithful alumni of our alma maters. We create fabricated narratives about who we are, and repeat these fanciful symbolic tales to ourselves, until we believe them so fully that we forget the absolute horror of our impending fates.

“What does it mean to be a self-conscious animal? The idea is ludicrous, if it is not monstrous. It means to know that one is food for worms. This is the terror: to have emerged from nothing, to have a name, consciousness of self, deep inner feelings, an excruciating inner yearning for life and self-expression – and with all this yet to die”.

Most men are content to spin the cocoon of the causa sui project so tightly around themselves that they forget that the symbolic self was a fabrication and that the physical self is the reality. It is notable that humans are the only animals capable of spinning this cocoon, as we are the only animals who are conscious of our future termination. This becomes the nexus for some individuals collapsing under the weight of the fallacy of symbolism and succumbing to suicide, an act that is unique to human beings. Mental health is where the real genius of Becker’s work shines. This is especially true from his chapter “A General View of Mental Illness,” where he explores psychiatry through the lens of depression and schizophrenia. What is so fascinating about this chapter is that it, for the first time, made me consider that those we deem mentally ill may be the only sane people on this planet. Becker does this by highlighting the individual who paves his own path in the journey of death anxiety – the creative

individual.

“Existence becomes a problem that needs an ideal answer; but when you no longer accept the collective solution to the problem of existence, then you must fashion your own. The work of art is, then, the ideal answer of the creative type to the problem of existence as he takes it in – not only the existence of the external world, but especially his own: who he is as a painfully separate person with nothing shared to lean on.”

Becker is roughly bestowing the term artist on any individual who is willing to take on “the burden of his extreme individuation” by rejecting the laundry list of pre-made, society approved, immortality projects to conquer death anxiety on his own terms. Why the artist could not be content to assume the characterology of a birdwatcher and derive meaning from an already extant causa sui project is beyond the scope of the discussion. However, once an individual finds themselves in the situation of personal isolation, they are now outside the safe boundaries of society and must answer for it.

“As soon as a man lifts his nose from the ground and starts sniffing at eternal problems like life and death, the meaning of a rose or a star cluster – then he is in trouble. Most men spare themselves this trouble by keeping their minds on the small problems of their lives just as their society maps these problems out for them.”

Becker touches on mental illness as a kind of “failed heroics” when an individual is not able to fulfill their immortality project. He covers this with individuals suffering from depression and from schizophrenia. For those who are depressed, they can see through the veil that their own immortality projects are failing. This leaves them stripped of the symbolic self and forced to own up to the physical self and the death anxiety that ensues. “It is so natural to try to be heroic in the safe and small circle of family or with the loved one,” but what if this heroism backfires and what was safe and secure betrays you. Without this security, the depressed person has nothing to offer to the cosmos as an immortality project – that is the realm of creative individuals. “When the average person can no longer convincingly perform his safe heroics or cannot hide his failure to be his own hero, then he bogs down in the failure of depression and its terrible guilt… the last and most natural defense available to the mammalian animal.” The depressed person resorts to a state of infancy in his inability to execute his hero narrative, almost as a plea for the universe to accept the individual at present state as it was when it came into the world.

If depression is a complete resort to the physical self, with abandonment of the symbolic, then schizophrenia is the exact opposite. In schizophrenia, “your symbolic awareness floats at maximum intensity all by itself.” Schizophrenics deny the very physical reality that others seem to be experiencing in pursuit of their own symbolic immortality project. They see, hear, and perceive things that no one else can. They assert grandiose ideas of personal necessity with little to no regard for the shared narratives of others. They are, in a sense, “pure heroes” – living inside a mental state that is both superior to their physical bodies and to the realities of the cultures in which they are situated. While the depressed individual is painfully aware of the failure to fulfill their heroic, the schizophrenic views themselves on the other end of the spectrum, where all meanings are subsidiary to their heroic narrative. Becker asserts that the only trait separating an artist (in the cultural sense) and a schizophrenic is the talent to channel the heroic narrative into a creative project that can be appreciated by others. One need only to recall the great Vincent van Gogh to realize that this is true in every possible sense.

Those deemed mentally ill by society are those who could not conform to “normal cultural heroism”. They have failed, in unique ways, in their own heroic projects – and subsequently become a burden on others in society. Had they only been content to be bird watchers or NASCAR fans, they could have found a place in society. But this is where the perceptive reader will truly take a pause. The depressed individual, schizophrenic, artist, and normal cultural hero are all heading towards the same cesspool of death and decay regardless of how they choose to approach it. It would be one thing if each person could maintain his own immortality project without it coming into conflict with another’s project, but we know that this is not the case. In fact, most immortality projects are diametrically opposed. Who, then, is the true heroic individual?

I will, of course, leave that discovery up to the reader. I cannot say enough good things about this book – it is one of the truly personally challenging books that I have read in my life. One that cannot be read as a passive interest because it speaks so personally to the soul of being itself. It will certainly leave you feeling uneasy and unsettled, and I warn that it is not for the faint of heart. But it is rich beyond belief, a fertile bed of truths so tangible you feel as if the very soil of the universe is sifting through your fingers. I will leave you with a caveat emptor from the book:

“What joy and comfort can it give to fully awakened people? Once you accept the truly desperate situation that man is in, you come to see not only that neurosis is normal, but that even psychotic failure represents only a little additional push in the routine stumbling along life’s way. If repression makes an untenable life liveable, self-knowledge can entirely destroy it for some people.”

Written by Cal Wilkerson

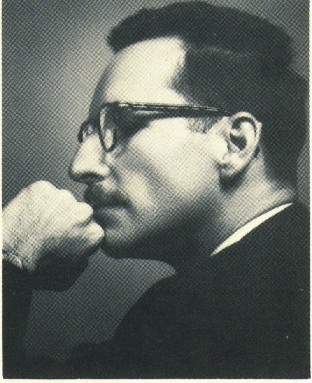

Ernest Becker Grave