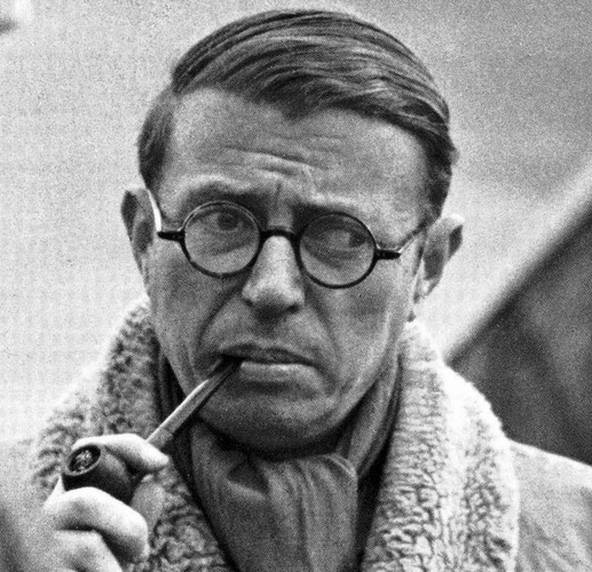

“Man is condemned to be free; because once thrown into the world, he is responsible for everything he does.” Thus espoused the monumental French philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre. Of course, the man would arguably have never reached the soaring heights of popularity that he achieved in the 20th century without the company of his mademoiselle, Simone de Beauvoir. Meeting in 1929 and remaining together in an open, noncommittal relationship throughout the entirety of their lives was a testament to this fragile, strange, and exhilarating new philosophy of existentialism that has woven itself into the fabric of society ever since. Sarah Bakewell, in her book “At the Existentialist Café: Freedom, Being and Apricot Cocktails” begins and ends with this royal couple of existentialism, tracing out the cast of characters that contributed to and solidified it along the way.

Bakewell’s style is unusual and at times disjointed – she follows a dizzying number of individuals over multiple decades to elucidate a branch of philosophy of which the architects potentially do not fully understand themselves. The book fluctuates from crystal clear portraits of these figures to muddled, fragmented accounts of events occurring throughout France and Germany from 1910-1960 that did not fully hold my attention. While the approach of Bakewell is unconventional, the ideas and individuals weaved into her pages were more than worth the effort expended, and I recommend a healthy dose of perseverance. This succinct, beguiling account will perplex and stimulate you, making you wonder what all this existential fuss is about. In the end, you will find a plethora of application for your own life and reconsider what it means to be a free, existing thing.

I could not possibly hope to flesh out the full history of existentialism in this post, but I will attempt to provide a snapshot. 19th century Danish philosopher Soren Kierkegaard (of whom I have posted before) ushered in the age of existentialism by introducing his audience to concepts such as the anxiety that comes from a seemingly limitless number of choices. In one of his most famous quotes, he tells us that “anxiety is the dizziness of freedom.” Once a man becomes self-aware of his freedom to choose from a limitless number of options, he is also aware that he is unaware of the equally limitless number of consequences that may come from that choice, and he is also aware that he is unaware to know what the right choice to make is until after the fact of his choosing. Sound confusing? Such is existentialism, and it plunges its proponents into a paralyzing, dizzying anxiety that threatens to spiral out of control. It is much like going to a restaurant with an infinite menu and not even having an inclination of what you would most enjoy eating before receiving the menu that you did not know had so many options. The only thing that is certain is that you must choose something, and the unknown consequences of your choice. For even the decision to not choose is a choice in itself, and so forth.

From Kierkegaard, a brief expose into Nietzsche, Hegel, and Dostoevsky leads to the birth of the German phenomenology. The giants of this branch of philosophy – namely Husserl and his protege turned opponent Heidegger – attempted to minimize the anxiety of choice through the painstaking description of every phenomenon in the world. Heidegger attempted to bring us “back to the things themselves”, as if the most pinpoint, air-tight description of everything that can be consciously experienced with our senses would in some way reveal the purpose of the things themselves. The frustrating thing about phenomenology is that you must never let the query of an object’s purpose enter in to your conscious examination of it while attempting to describe it, because then you will lose sight of the thing itself and not be fully capable of describing it. The complexity of Heidegger’s thoughts many never truly be ascertained, and once he sided himself with Nazi sympathies he lost much of his credibility in the intellectual world and retired to his German hamlet in Todtnauberg to describe things and fade into madness and obscurity. Nevertheless, while a prisoner of war in 1940-41 Sartre read Heidegger’s “Being and Time” and became enraptured with the concept of the experience of being that is peculiar to humans, that which Heidegger referred to as “dasein”.

Sartre was inspired to write his own magnum opus, “Being and Nothingness: A Phenomenological Essay on Ontology”. Here, Sartre made his central premise that “existence precedes essence”. Every artifact is presumed to have a purpose for its being before it becomes (existence). No fork has ever been made without the understanding first that its existence is necessary for the consumption of food. After that fact has already been established, then the fork is made and is used for the essence of its existence. On the contrary, Sartre asserted that “man first of all exists, encounters himself, surges up in the world – and defines himself afterward”. For Sartre, there is no prior essence to the existence of a human being. Once a human becomes aware of his existence, he must then define his essence through a series of choices that he makes throughout his life of which he is personally responsible. These choices are neither right nor wrong, they simply are, and a man is free to choose whatsoever he wishes. Any meaning or purpose that comes along the way is that which the individual assigns to his choices, and he is free to assign or not assign meaning to the limitless options available to him daily. The only thing that cannot be shirked is responsibility for the choices made, as it is the choice itself that is the essence of existing.

While ultimately born from the mind of a Christian philosopher (Kierkegaard), this outlook on life is diametrically opposed to the notion of human purpose imbued by his Creator that has characterized Western thought for thousands of years. Sartre’s thinking was far from the necessary conclusion of Kierkegaard, but his polyamorous relationship with de Beauvoir and intellectual rebellion amidst a conservative and Catholic France was a testament to his belief in the absurdity of a world devoid of essentiality. Contemporaries Albert Camus and Maurice Merleau-Ponty started with the same raw material and drew vastly different conclusions from Sartre and de Beauvoir, but all these philosophers remained captivated by the dizziness of freedom that was first offered to them by Kierkegaard. They were also variously influenced by the socio-political turmoil of the first half of the 20th century, living through the horrors of two world wars, and attempting to construct a philosophy out of a world that no longer seemed purposeful to them outside of their ability to choose. Camus, a French-Algerian national whose country crumbled to insurrection and threatened the life of his family, poignantly reflected that “life is the sum of all your choices”.

“At The Existentialist Café” is a difficult work, full of ideas that are practically incomprehensible and flawed, conflicted individuals who devoted their entire mental faculties in the pursuit of purpose amidst a sea of choice. I do not agree with all of what these men and women believed, but the impact of their ideas both in the world in which I live and in my own life personally are undeniable. de Beauvoir sparked the feminist movement with her “The Second Sex”, and any exploration of an internet search engine will reveal millions of humans attempting to predict the outcome of the sum of their individual choices. Each day I awake to a world where I must make innumerable choices and live with the outcomes. I will never know if I chose correctly, what pleasures could have been afforded and pains avoided if I had chosen differently. It is impossible to know if I will arrive at a destination that I ascribe meaning to, but at the center of it all there is one certainty – that I must choose. That man is a choosing thing. What is existentialism? Sartre responds in full: “existentialism’s first move is to make every man aware of what he is and to make the full responsibility of his existence rest on him.” I hope that those who choose to read this book enjoy it as much as I did, but of course, the choice is yours -and the choice to not choose to as well!

Written by Cal Wilkerson

Jean-Paul Sartre