To quote from the beginning of the preface of With the Old Breed: this is “an account of one Marine, E. B. Sledge, in training and in combat with Company K, 3d Battalion, 5th Marine Regiment, 1st Marine Division during the Peleliu and Okinawa campaigns.” Young and old men taken far from Mobile, Alabama, or anytown, U.S.A., to tiny islands no American had ever glanced on a map, much less ventured before, to conquer and defeat “the enemy.” Partially recreated for a contemporary audience in HBO’s The Pacific, Sledge’s war-time memoir is a faithful and sobering account of the enlisted Marine, and much more.

Though he speaks and acts throughout his battles through various roles–private, stretcher bearer, recruit, etc.–it is often his position as 60 mm mortarman, the weapon he chose seemingly at random in basic training, that tends to inform the perspective most. Sledge, by the end of the work, by most measures, has become an expert marksman–but just one man trained “to be cannon fodder in a global war that had already snuffed out millions of life.” Perhaps no other war-time account is as vivid in placing the soldier in the throes of “shell shock”. The constant noise and concussion of shelling even weary the reader. Whether charging across an open field, or exchanging a counter barrage with the Japanese, the bombardments are not strategic abstractions, but graphic descriptions of human bodies, bathing in a steaming shower of hot metal, moving in shrapnel and bullets that cut flesh, mangle limbs, and draw blood.

Here, Sledge’s recollections, which he largely captured in notes taken inside a small sweaty Gideon’s Bible, are an old and new testament to the awesome and terrifying capacity of humanity hard at work in one of its oldest endeavors, “killing for the sake of killing.” Sledge becomes a man—by his own admissions and actions, (though his acts are not as foul as some of the other Marines and Japanese accounted)—desensitized to the carnage around him: every day, witnessing “some new, ghastly, macabre facet in the kaleidoscope of the unreal.” After the blood, the maggots, the stinking uncovered corpse or corpsmen left to rot in mud and filth, Sledge is forced to question the “eloquent phrases of politicians and newsmen about how ‘gallant’ it was for a man to ‘shed his blood for his country’, and to ‘give his life’s blood as a sacrifice,’ . . . . The words seemed so ridiculous.” Men seem to be damned by features of geography, moved here and there in formation on maps and battle plans (which are recounted and sketched in impressive detail by the author), where “only the flies benefitted.” He accounts an unholy communion of man and nature, creature and machine, that mortifies hope.

In the final pages and stages of Okinawa, Sledge and the reader must encounter a rotting Marine inside a killing field crater: “the most ghastly skeletal remains I had ever seen”, a “half gone face”, leering with a sardonic grin seemingly mocking his efforts to hang on to life. Or, as Sledge notes, “maybe he was mocking the folly of the war itself: ‘I am the harvest of man’s stupidity. I am the fruit of the holocaust. I prayed like you to survive, but look at me now. It is over for us who are dead, but you must struggle, and you will carry the memories all your life. People back home will wonder why you can’t forget.’” And for Sledge, these recollections are absolutely necessary and well recalled: informed, exact, humorous at times, and uncompromising–his existential meditations are important and timely placed. Such tales of war are universal, and both young and old; all seem to make young men old, and old men young.

Why does this book matter? Facing our depravity, when man struggles with those who can kill both body and soul, here, it is thought, word and deed, and the stories of those he memorializes who were willing to make a sacrifice, that may, though even in part, serve to resurrect some part of the human spirit from dirt, decay and death. If man has and will go so low, may we be witnesses, even in our imperfect and ironic attempts, of preserving life, to some understanding of true life, and to have that life more abundantly. As he ends, “the only redeeming factors were my comrades’ incredible bravery and their devotion to each other. Marine Corps training taught us to kill efficiently and try to survive. But it also taught us loyalty to each other–and love.” He closes: until the millennium arrives and man ceases to enslave another, true valor and sacrifice will have men to test its meaning. And with that esprit de corps, the memories of “the Old Breed” will not and should not soon be forgotten.

Written by guest author Garrett Wilkerson

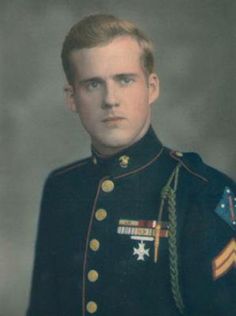

Corporal Eugene Sledge