Being a man of supernatural persuasion, I reject the most central premise of Carl Sagan’s Cosmos; however, my dismissal of Sagan’s naturalistic cosmology does not in any way diminish the haunting beauty of his masterpiece. The universe itself was Sagan’s god, and he worshipped its complexities and intricacies that could be understood only through the powerful tool of the scientific method. “The Cosmos is all that is or was or ever will be. Our feeblest contemplations of the Cosmos stir us — there is a tingling in the spine, a catch in the voice, a faint sensation, as if a distant memory, of falling from a height. We know we are approaching the greatest of mysteries.”

Sagan’s reconstruction of cosmological history follows that which is generally accepted by academic science today: all of the matter and energy contained in the universe as we know it came bursting forth from a singularity known as the Big Bang some 13.8 trillion years ago. Our earth formed around 4.6 billion years ago, and life on earth emerged shortly thereafter, 3.5 billion years ago. It is estimated that 99% of all life that ever inhabited the earth is now extinct. After several million years of evolution, our species, homo sapiens, appeared on the scene 2.2 million years ago. On the cosmological timescale, human beings are newcomers to the grand scheme. However, we are unique in that we are the only beings discovered that have consciousness. This consciousness is “a way for the universe to know itself.”

Taken from the perspective of a naturalistic atheist, this narrative is full of spectacular wonder. Through millions of chance occurrences, not orchestrated or planned for, Sagan (and all of humanity, he asserts), arose as a cosmic accident at this particular moment in the passage of time. The very elements that compose human beings came from the blazing hot furnaces of stars. “The nitrogen in our DNA, the calcium in our teeth, the iron in our blood, the carbon in our apple pies were made in the interiors of collapsing stars. We are made of starstuff.” In a sense, human beings are the first awakening of the cosmos to itself… or perhaps not. Sagan holds out hope throughout the book that, given the vastness of the universe, there might be life and even conscious life on other planets. It is his vision for humanity that we put aside our petty differences, form a truly cosmopolitan, global society, and devote our resources to the exploration of the universe from which we came. Harkening back to the great Age of Exploration, he calls our planet “the shores of the cosmic ocean” and invites us on his interstellar journey of epic proportions.

Cosmos is the manifesto of a thoughtful, humanitarian atheist. Far from being a purely scientific treatise, his work ventures deeply into the realms of philosophy and religion as well. He upholds and protects the dignity of human life with scientific justification. “Every one of us is, in the cosmic perspective, precious. If a human disagrees with you, let him live. In a hundred billion galaxies, you will not find another.” Living in a time of likely nuclear self-annihilation during the height of the cold war, Sagan was a pacifist who was very concerned about the future of humanity. He saw history as progressive and believed that the march of scientific progress could usher in a golden age of human prosperity. As an atheist with no hope of an afterlife, Sagan devoted himself to living as full and meaningful a life as possible. His work inspired future scientists such as Neil deGrasse Tyson. His wife, Ann Dryan, when asked about her husband’s death, responded: “We never trivialized the meaning of death by pretending it was anything other than a final parting. Every single moment that we were alive and we were together was miraculous-not miraculous in the sense of inexplicable or supernatural. I don’t think I’ll ever see Carl again. But I saw him. We saw each other. We found each other in the cosmos, and that was wonderful.”

Regardless of your religious convictions, this is a book worth reading. It will challenge any reader’s self-importance and humble him in the face of the awe-inspiring cosmos. We are so much smaller and more insignificant than we pretend to be. We are subject to and at the mercy of forces wildly outside of our control. Hubris has no place in the face of galaxies, pulsars, and black holes. Perhaps Sagan would even agree with the third chapter of the book of Genesis, albeit with a slight caveat. Stardust you are, and to stardust you shall return.

Written by Cal Wilkerson

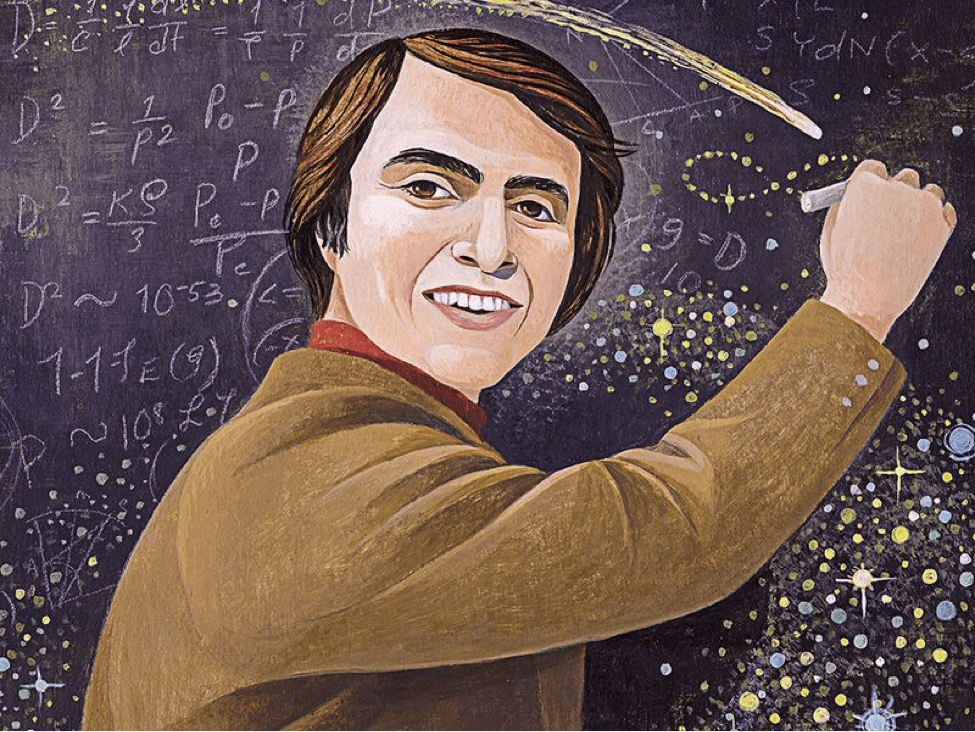

Carl Sagan