Since I am living a year in Africa, I thought it would only be proper to read and review some African literature. Admittedly, I have never read any works of literature from or about Africa aside from King Solomon’s Mines (if that even counts). The book I picked for my introduction to the genre, Cry, the Beloved Country, certainly did not disappoint.

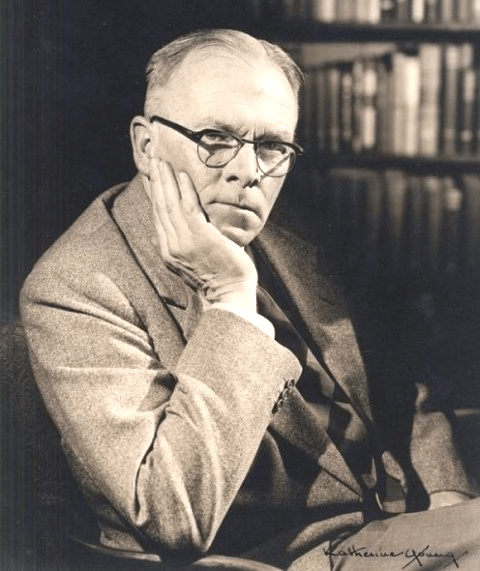

This work was written by Alan Paton, a former principal for a South African boy’s reformatory school, in 1948. The book is a work of historical fiction, and it details the journey of Reverend Stephen Kumalo, an Anglican village priest from Ndotsheni in the province of Natal. Reverend Kumalo receives a letter at the beginning of the novel requesting that the old priest come to Johannesburg on account of his sister, Gertrude, being sick. Having also not heard from his son Absalom, who left for Johannesburg some time prior, Reverend Kumalo decides upon the costly and lengthy trip to the city. This trip to Johannesburg leads Kumalo on a journey that will threaten to unravel him – as he witnesses firsthand the deleterious effects that the city has had on his closest loved ones, as well as the poor state of affairs for race relations in South Africa just before apartheid.

This book has so many rich themes that it is impossible to plumb the depths of them all. I can only enumerate a few and highly recommend that you pick up a copy of the novel for yourself. Passages of the book are reminiscent of the Bible, and they raise the questions of futility of life and suffering. While Kumalo searches in vain for his son, he cries out: “who indeed knows the secret of the earthly pilgrimage? Who knows for what we live, and struggle, and die? Who knows what keeps us living and struggling, while all things break about us?” Melodic passages like this are scattered throughout the book, and they offer a window into the pain that was felt in this period of time as native villagers were pulled into horrible working conditions in Johannesburg with the allure of the mines. The gold mines offered to enrich South Africa, but at the end of the day, they only served to enrich wealthy white Europeans while the native workers lived in Shantytowns and faced moral degeneration. Such degeneracy in his own sister and son is what Kumalo sadly had to face when he found them in Johannesburg.

The themes of race relations between black and white in this book are prophetic, reaching even into the present day South Africa. They apply not only to South Africa, however, but even to America and beyond. Consider this passage: “For we fear not only the loss of our possessions, but the loss of our superiority and the loss of our whiteness. Some say it is true that crime is bad, but would this not be worse? Is it not better to hold what we have, and to pay the price of it with fear?” Alan Paton, as a white principal of a boy’s reformatory school, understood the narrative of crime and fear all too well. His question for his country concerned the motives for native on white violence, and he summarized this motive as one of fear. Fear takes a primary place in the book – the whites of South Africa feared losing their superiority over the natives, and the natives feared their own relegated place in what was once their home country. Paton narrates a city hall meeting on what to do about native crime: “And our lives will shrink, but they shall be the lives of superior beings; and we shall live with fear, but at least it will not be a fear of the unknown”. To educate and lift the natives out of poverty would aggravate the existing social structure and usher in the unknown; the whites would prefer to live with fear of native crime rather than the fear of this new societal order.

There is a criminal trial in the book in which Paton explores fascinating themes of the relationship between the Law, the Judge, and the People. “The Judge does not make the Law. It is the People that make the Law. Therefore if a Law is unjust, and if the Judge judges according to the Law, that is justice, even if it is not just. Therefore if justice be not just, that is not to be laid at the door of the Judge, but at the door of the People, which means at the door of the White People, for it is the White People that make the Law.” I can’t help but read these words that were written in 1948 and think how deeply they would resonate with current political figures decrying social inequity in America today. Paton wrote with a masterstroke that cannot be denied – regardless of which side of the racial-political issues one sits.

In some ways the book is a theodicy, seeking to understand the very will of God. Kumalo has his own faith tested through his journey in Johannesburg, and towards the end he is admonished by a friend that suffering is the key to true belief. “For our Lord suffered. And I come to believe that he suffered, not to save us from suffering, but to teach us how to bear suffering. For there is no life without suffering.” The journey of Kumalo brings the reader face to face with much pain, and his response to adversity is remarkable.

Perhaps the most significant character in the book is not a human, but the land itself. The pivotal passage of the book goes thus: “Cry, the beloved country, for the unborn child that is the inheritor of our fear. Let him not love the earth too deeply. Let him not laugh too gladly when the water runs through his fingers, nor stand too silent when the setting sun makes red the veld with fire. Let him not be too moved when the birds of his land are singing, nor give too much of his heart to a mountain or a valley. For fear will rob him of all if he gives too much.” This exposition can make the heart soar and ache simultaneously – and it begs the central question of colonialism and imperialism: who has a right to the land? What gives anyone the right to claim for themselves a land, especially when there is an indigenous peoples already there? Are those indigenous peoples culpable for taking the land from those who dwelt there before them? Is this why the right of conquest has been historically understood as the foundation for what is just? Answers to these questions, as well as numerous other quandaries can be found within the pages of this famous and important South African novel.

Written by Cal Wilkerson

Alan Paton