As far as vicarious living is concerned, John Krakauer recounted one experience I never wish to personally have but felt as if I have had – due to the vividness of his writing. Into Thin Air is an autobiographical account of his time on Mt. Everest during the spring of 1996. Krakauer was sent by Outside magazine to Nepal to write about the commercialization of Everest as part of famous alpinist and climbing guide Rob Hall’s expedition. Krakauer was never meant to proceed any further than Everest Base Camp; his decision to do so involved him in a tragedy that will likely haunt him until the day he dies. Four members of Rob Hall’s “Adventure Consultants” team died in the summit attempt, including Hall himself. As a journalist and a client of the expedition, it was natural for Krakauer to attempt to maintain objectivity, but while personally witnessing fellow clients and his own guide perishing at an altitude of 28,000+ feet, he will always wonder if he should have done more to attempt to save them.

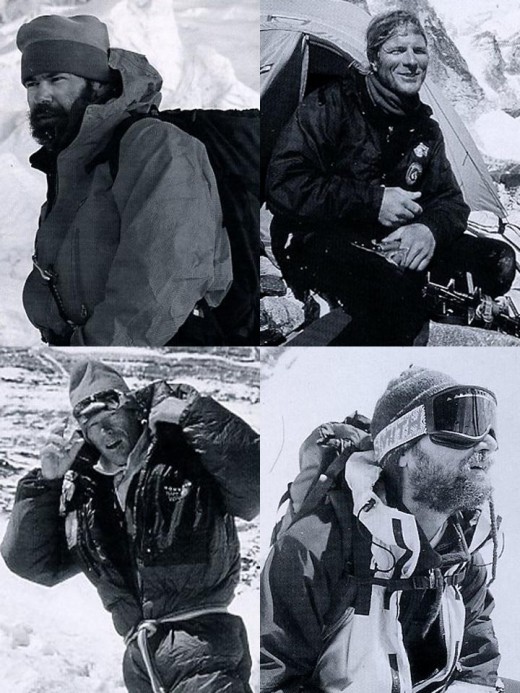

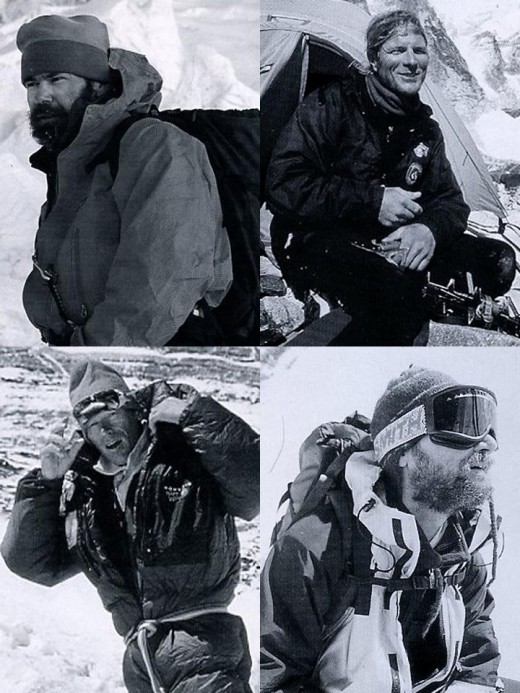

So many themes captivated me from this book, but a few were especially prominent. Krakauer does an incredible job of making the various guides for the expeditions come alive as human beings, and not just as names in a book. Rob Hall, Scott Fischer and Anatoli Boukreev will forever remain demi-gods to me. I have never done alpine mountain climbing, but after reading the feats that these men accomplished over their careers, I am confident that they were some of the most gifted and underappreciated athletes of the 1990s.

At the time of the expedition, Rob Hall had just completed his 5th summit of Everest, the most at that time of any other non-Sherpa mountaineer. His first date with his future wife, physician Jan Arnold, was a summit of Denali in Alaska. Scott Fischer, leader of the friendly rival alpine outfitter Mountain Madness, climbed Lhotse (27,950 feet), K2 (28,251 feet), and Everest (29,029 feet) all without supplemental oxygen. Those are the 4th, 2nd, and 1st highest peaks in the world, respectively, climbed with 66% less oxygen than we enjoy at sea level! He employed his great friend Anatoli Boukreev as a lead climbing guide for Mountain Madness on the Everest expedition. The apotheosis of Boukreev came for me upon realization that he had climbed 10 of the world’s 14 eight-thousand-meter peaks (peaks above 26,247 feet) WITHOUT supplemental oxygen. The interplay of these three guides really formed the crux of the book’s tension.

Most tragically, Krakauer got exactly the story that he came to write. Ever since Dick Brass, a ultra-wealthy Texas rancher, became the first person in world history to climb the “Seven Summits” (a concept that he created) at age 55 in 1985, the commercialization of these peaks began. If some old former Disney owner could climb the highest point on each continent, then the challenge was up for grabs for anyone with enough time and money to do it, right? The tragedy recounted in Into Thin Air and the point that Krakauer successfully makes after experiencing it firsthand is that many of the world’s summits, and especially the Himalayan ones, should remain the exclusive realm of the alpine demigods. Mere mortals have no place on these peaks, and an abundance of wealth cannot redeem your life from a sudden change of weather or an avalanche at 29,000 feet.

The average price paid in 2017 for an Everest attempt, not including travel to and from the mountain or personal effects, was roughly $45,000. Krakauer does an admirable job of relating this steep price tag to the poor decision making on the part of some of the guides to not turn around when so close to the summit. Some of the clients were making their second or third summit attempt, and at this point in their lives, death would be preferable to not reaching the summit. Additionally, in the last 2,000 feet of the climb, the oxygen in the air is about 33% what it is at sea level. Krakauer reports of men in the expedition hallucinating, not getting enough oxygen to the brain to make sound decisions, and not having enough oxygen in the blood to protect against the sub-zero temperatures. Additionally, each guide fears that if they do not get their clients to the top, then future clients will choose the rival expedition with the highest summit success rate, safety be damned.

The story reaches its climax on the fateful night of May 10th as eight people caught in a blizzard died on the mountain in an attempt to descend from the summit. The account of their lying out in the agonizing cold getting pounded by the blizzard, and of the heroism displayed by the guides in attempting to (and in a few cases successfully) save those stranded is both beautiful and terrible. Of course, the most poignant question remains of whether Anatoli Boukreev is a selfish monster or a selfless hero, but that is for the inquisitive reader to decide for himself. The post-summit fallout between Boukreev and Krakauer is sad as it is painful, and for the record – I agree wholeheartedly with Krakauer, although I am in awe of the accomplishments and career of Boukreev.

As Krakauer stood on the summit of Mount Everest, after 6 weeks of acclimatization and grueling hiking, not to mention months and years of preparation, he admits that he “just couldn’t summon the energy to care”. How remarkable to me, that a man would put his body through hell and back all for an overwhelming surge of… apathy. He hadn’t slept in 57 hours; he had only eaten a bowl of ramen noodles and a handful of peanut M&M’s in the preceding three days. He could feel nothing “except cold and tired”, and the lack of oxygen (even while wearing supplemental oxygen) reduced his mental capacity to that of a “slow child”. For the $65,000 Outdoor magazine paid to get him there, he spent “less than 5 minutes on the roof of the world”.

Krakauer is the greatest adventure writer of our day, bar none. Every chapter is the work of a master craftsman who imbues each sentence with his very soul, as one who has literally experienced the pain and danger himself. He exposes unchecked romanticism about adventure for what it truly is – a fool’s game, that costs lives. For anyone with wild dreams of grand outdoor adventure, myself notwithstanding, take a detour through Krakauer’s book and count the cost, before you succumb to illusions of grandeur.

Written by Cal Wilkerson

Left to right: Hall, Fischer (top) Boukreev, Krakauer (bottom)