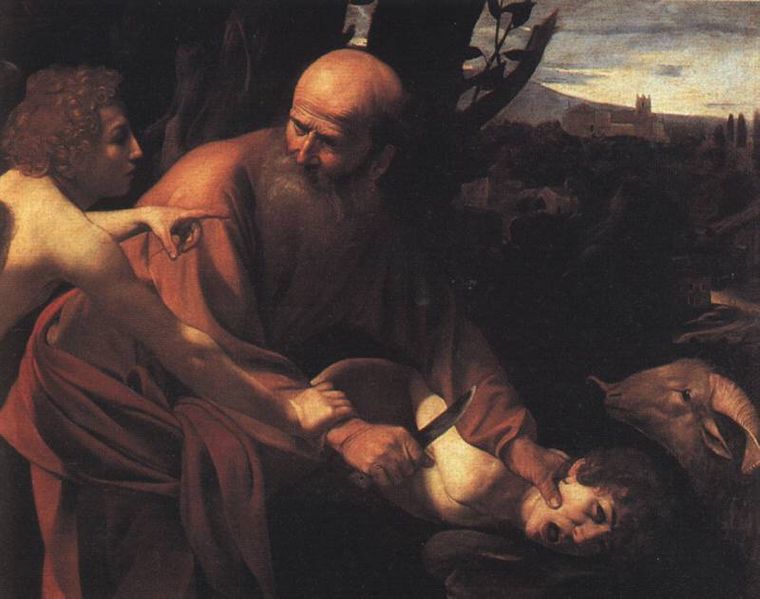

Since reading Soren Kierkegaard’s Fear and Trembling, the philosophical school of existentialism has had a growing influence on my thinking. While my understanding of existentialism is far from adequate to speak on it broadly, I can humbly attempt to convince the casual reader why this masterpiece of Kierkegaard’s is worth a week of your time to read. Written in 1843 by the Danish philosopher, the book focuses on the Biblical account of Abraham being commanded by God to murder his only son Isaac as a sacrifice to the divine. At first glance, the reader may be off put that this is simply another attempt at moralizing by a Christian philosopher, but this is hardly the case. Kierkegaard ingeniously uses the patriarch’s struggle of faith as a pseudo-autobiographical account of the breaking from his own engagement to Regine Olsen.

Using the pseudonym of Johannes de Silentio, Kierkegaard begins his work with a Eulogy on Abraham. Laying out his central premise, he espouses, “everyone shall be remembered, but everyone was great wholly in proportion to the magnitude of that with which he struggled. For he who struggled with the world became great by conquering the world, and he who struggled with himself became great by conquering himself, but he who struggled with God became greatest of all.” Herein lies the existential nature of the work, that of the struggle of personal existence against external forces. God is primary in this existential struggle, as He is the one force against which the individual existence has no real choice but submission, even a submission against one’s will.

Kierkegaard next presents three Problemata’s which Abraham had to answer to become the great man of faith that he is revered as. He had to gain this reverence, for other men doing the exact same thing that Abraham did would be considered sinful. How is it that Abraham could purpose in his heart to murder his son, his only son, and yet still be revered as a great man?

The first problem that Kierkegaard poses is whether Abraham had a right to a teleological suspension of the ethical. Abraham had to choose between what was ethical (his duty as a father and a husband) and subservience to a telos (the ultimate, that being God). When God gives a commandment, the ethical no longer applies, and what is wrong in a normal sense now becomes right in an ultimate sense. This paradox that what is wrong is also right, and what is right is also wrong, is central to the next problem that had to be addressed – namely whether Abraham had an absolute relation to the absolute. To become the knight of faith, as Abraham did, he had to make the leap of faith. This leap required both fear and trembling on the part of the potential knight, because what was being asked was absurd and should push a man to desperation. The existential is rooted in the freedom of choice, that of personal existence. A man must choose either to make the leap of faith, or to reject God on account of the paradoxical nature of God’s request. However, for Abraham to become the knight of faith, he had to accept his absolute duty to God and take the leap of faith in sacrificing Isaac.

The third and final problem that is addressed in the book is whether or not it was ethically defensible for Abraham to conceal his undertaking from Sarah, Eliezer, and Isaac. According to Kierkegaard, the world of ethics rewards disclosure and punishes hiddenness, while the world of aesthetics does the exact opposite. The task that God gave to Abraham was so terrible that he could not reveal what he purposed to do to anyone else, but because God commanded him to do it, he was afforded a teleological suspension of the ethical because of his absolute relation to the absolute. He was ethically wrong, but absolutely right. Abraham had every intention of murdering Isaac, going so far as to lift the knife and begin to plunge on Mount Moriah. He agonized the entire journey up the mountain, and never once revealed to Isaac, Sarah or Eliezer what he purposed to do. But he purposed to do it, and he struggled with an internal agony and torment of faith that few can comprehend. Perhaps Abraham’s silence was an outward expression of an inward reality that defies all comprehension.

What is central for Kierkegaard is not a moral story based in Judeo-Christianity, but rather a story that highlights the very struggle for existence. According to existentialism, when a man makes a decision, especially an agonizing one requiring much fear and trembling, that is when a person truly exists. Agency is the primary thing for the human being, and the magnitude of his struggle for agency defines his greatness. The story of Abraham takes primacy for Kierkegaard, becomes Abraham was forced into a situation in which he had to make ultimate decisions, not ethical ones.

Kierkegaard too made an ethically unpopular choice in favor of what he saw as a leap of faith towards the infinite. He broke off an engagement with his fiancé Regine Olsen, opting instead to make the movement of faith towards the infinite. What this looked like practically in the life of an existential philosopher, I can only speculate. It is fascinating to me that he compares the heart-wrenching sacrifice of an only son at the hands of his father to the sacrifice of breaking off his engagement in the face of no apparent external prodding. His family approved of the marriage and so to did his societal peers; it seemed to be a perfectly reasonable match in the finite sense. However, like Abraham, Kierkegaard had to conceal his absolute relation to the absolute from everyone else, and make the leap of faith alone. Whatever his reason, he felt personally compelled to act, and for that he must be commended.

In conclusion, this book is a treasure trove of thought-provoking philosophy for both the religious and the secular alike. In the end, it is a book about action and about decision. Great men are called to struggle with difficult decisions on a daily basis – whether with the world, with ourselves, or with a higher power. Great men are required to make decisions that at times defy what is ethical and what is conventional. Great men are given the freedom to recognize that at times, their decisions must rise to the plane of an absolute relation to the absolute, for which they are accountable to God alone. Great men earn the right to conceal their plans, to defy the ethical and realize that they owe an explanation for their actions to no one, save God. Great men are called to take the leap of faith into the infinite, to accept the paradox of life; to accept and leap anyways.

Written by Cal Wilkerson

![The_Sacrifice_of_Isaac_by_Caravaggio[1]](https://brainsandbrawn.blog/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/the_sacrifice_of_isaac_by_caravaggio1.jpg?w=518&h=408)

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio’s Sacrifice of Isaac