Of all works of literature I have been tasked with writing on, The Brothers Karamazov is far and away the most difficult. Even a cursory attempt to capture the magnificence of this book is tantamount to sacrilege. This magnum opus of Dostoevsky will strike even the casual reader as just short of divine inspiration. Nevertheless, with unskilled words and poor understanding of the work that I am handling, I will attempt to do just that. BK was completed by Fyodor Dostoevsky in 1880 – his final and most grand novel. It is written in four parts, subdivided into twelve books, and follows the drama of three brothers in the Russian village of Stepanchikovo at the turn of the 20th century. The three brothers are Dmitri, Ivan, and Alexei, one of which is culpable in the murder of their father, Fyodor Pavlovich, following a scandalous feud that flares up in a short number of days. The book ends with the trial of one of the brothers, a verdict, and an open-ended tale of his fate. BK is so much more than a simple murder mystery, however. At its core, it is an intense exploration of the conflicting identities of the enigmatic nation that is, and was, Russia. Each of the three brothers represents a unique and contradictory ideal of what Russia should be as it heads into modernity. Russia has always been an outlier, in so many ways. Its struggle for identity can be traced through many narratives: whether it is a Western nation or belongs more properly with the East, its lagging behind the rest of Europe in industrialization (not abolishing agrarian serfdom until 1861), its distinctively Christian hierarchy (choosing a variant of Greek Orthodoxy rather than answering to the Vatican), and of course, diving headfirst into Communism in 1917, far before the rest of Europe was prepared to do so. These tumultuous questions were raging inside the head of Dostoevsky, and his avenue of exploration for them was through his three protagonists. Alexei, the youngest brother, represents the naivety and enviable simplicity of continued faith in the God of the Russian Orthodox Church. He enters the local monastery as a novice under the instruction of the beloved Elder Zosima. The middle brother, Ivan, is the antithesis to Alexei. He has returned to Russia after an extensive stay in France, where he has learned the twin philosophies of atheism and socialism. He longs to see his Motherland turn from its backwards belief in a higher power, and join with the rest of Europe in the ideas of the Enlightenment. Dmitiri, the eldest, is the most like their father. He represents the primal and brutish nature of ancient Russia. A destitute voluptuary, Dmitri is guided only by his sensual pleasures, unable to restrain himself from the allures of wanton women, excessive spending, and overconsumption of cognac. While each of the brothers embodies a different aspect of the true Russian character, Dostoevsky did not hold them all in equal esteem. He indicates a clear intent for Alexei, affectionately called Alyosha, to be the reader’s protagonist. Alyosha’s path alone transcends questions intended solely for the future destiny of Russia and provided answers for the future destiny of mankind. His path cut to the heart of what it means to be human in a ragged, harsh and unforgiving world of other selfish human beings. His path was the “ideal way out for his soul struggling from the darkness of worldly wickedness towards the light of love”. He is also the glue holding all of the other characters together. His innocence and optimistic faith in the potential goodness of other human beings commands a respect that none of the other characters in the story come close to achieving. Alyosha draws all of his strength from the lessons of his superior, the Elder Zosima. The elders were an antiquated order in Russia at the time, and their ability to hold sway over the community was quickly losing traction due to rational empiricism and a discontinued belief in the supernatural. Alyosha, however, was a true believer. Zosima taught him not to focus on proofs or theorems. Scientific inquiry had no place in the realm of faith. Zosima exhorts, “no doubt is devastating. One cannot prove anything here, but it is possible to convinced… by the experience of active love”. Alyosha was taught to love and to love unconditionally. For Zosima, “each of us is guilty in everything before everyone, and I most of all”. His approach to faith was one of utter humility; convinced that he was the greatest sinner of all, greater than any fornicator, murderer, or wrathful man that ever lived, he possessed an inner peace and tranquility that no man could fathom save for those who also practice it. “A loving humility is a terrible power, the most powerful of all, nothing compares with it”. Ivan rages against the theology of Alyosha, and instead entrusts Russia with newfound philosophy. Sneering at Alyosha’s faith, he insists, “No animal could ever be so cruel as a man, so artfully, so artistically cruel”. Ivan cannot accept an omniscient, omnipotent, omnibenevolent and personal God within the world of unspeakable cruelty and injustice that he sees around him. “If the devil does not exist, and man has therefore created him, he has created him in his own image and likeness,” retorts Ivan. This represents a prevalent view within a cynical and disheartened Russia. The Russian aristocracy was tired of the peasant’s insistent faith in a higher power that had done nothing to mitigate the harsh realities of life. It is Alyosha’s role to redeem both his brothers (and metaphorically, Russia itself) from the hellish existence that socialism and atheism would usher in. “Fathers and teachers, I ask myself: “What is hell?” And I answer thus: “the suffering of being no longer able to love.” Reams of paper can and have been expended to plumb the depths of this book. The most I can do is close with some parting advice to the ambitious reader. You must read this book. There are lessons to last a lifetime within its pages. In the words of deceased author Kurt Vonnegut Jr., “There is one other book, that can teach you everything you need to know about life… it’s The Brothers Karamazov by Fyodor Dostoyevsky, but that’s not enough anymore.” A laundry list of world-class thinkers has had a similar response, including Albert Einstein, Sigmund Freud, Albert Camus and Aldous Huxley. The chapters “Rebellion”, “The Grand Inquisitor”, “From Talks and Homilies of the Elder Zosima”, and “The Devil. Ivan Fyodorovich’s Nightmare” are of such a sublime nature, that I cannot find adequate words to represent their utter literary ingenuity. Reading this book will test your endurance like no other work has. It took me a full 3 months to finish it, carefully pouring over every sentence, line by line, at no greater pace than 20 pages a day. Like all great works of art, it is meant to be savored. One could not truly unlock all of the treasures BK has to hold with ten read-throughs, but any self-respecting literature buff must try. Get to know the brothers. They will teach you more about yourself than any other literary character can.

Written by Cal Wilkerson

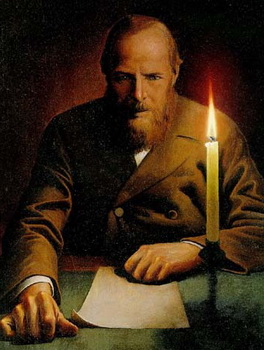

Fyodor Dostoevsky